God is eternal, unchanging, all-knowing, blessed, and sovereign. Yet Scripture describes him apparently changing his mind, regretting, and grieving (Gen. 6:6, 1 Sam. 15:11, Eph. 4:30). How are we to make sense of this? Don’t these texts undermine all that God is? And if they do, then shouldn’t we reevaluate our doctrine of God? The answer, paradoxically, lies in the doctrine that God’s emotions don’t change. Yet far from handwaving these texts, this doctrine, rightly understood, actually deepens their gravity.

In my last article, we established that God is simple—without parts, fully himself in all that he is. Not only that, but God’s action is simple—he always acts in all that he is. But we can press further still. If God’s being is without parts and his action is undivided, then his affection must also be simple: God feels—enjoys, delights in, loves, glories in, and burns for—all that He is. The intensity of God’s affection is as unfathomable as his being, and it is fully engaged in everything he does. Come with me as we plumb the depths of what this means.

All that God Is

If all of God is affectionally active in every moment, and every action, what does Scripture reveal about who God is? What affections does God have in Himself independent of any relation to creation? Divine simplicity teaches us that these two things are really the same question: what God is in himself is identical with his affection in and toward himself.

Scripture testifies that God is good, holy (Isa. 6:3; Rev. 4:8), loving—indeed, that he is love itself (1 Jn. 4:8, 16)—infinite (Ps. 147:5), omnipotent (Rev. 19:6), eternal (1 Tim. 1:17), and unchanging (Mal. 3:6)—among many other things. Likewise, Scripture testifies that God has strong, burning affections. God is said to “rejoice” (Jer. 32:41), “love” (John 17:26; 1 Jn. 4:8), and even “sing” for joy (Zeph. 3:17). In many cases, there is a direct parallel between Scripture’s testimony to God’s attributes and its description of his affections. For example, God loves (Jn. 3:16, 17:26) because he is love (1 Jn. 4:8). He rejoices because in himself, he is the fullness of joy.

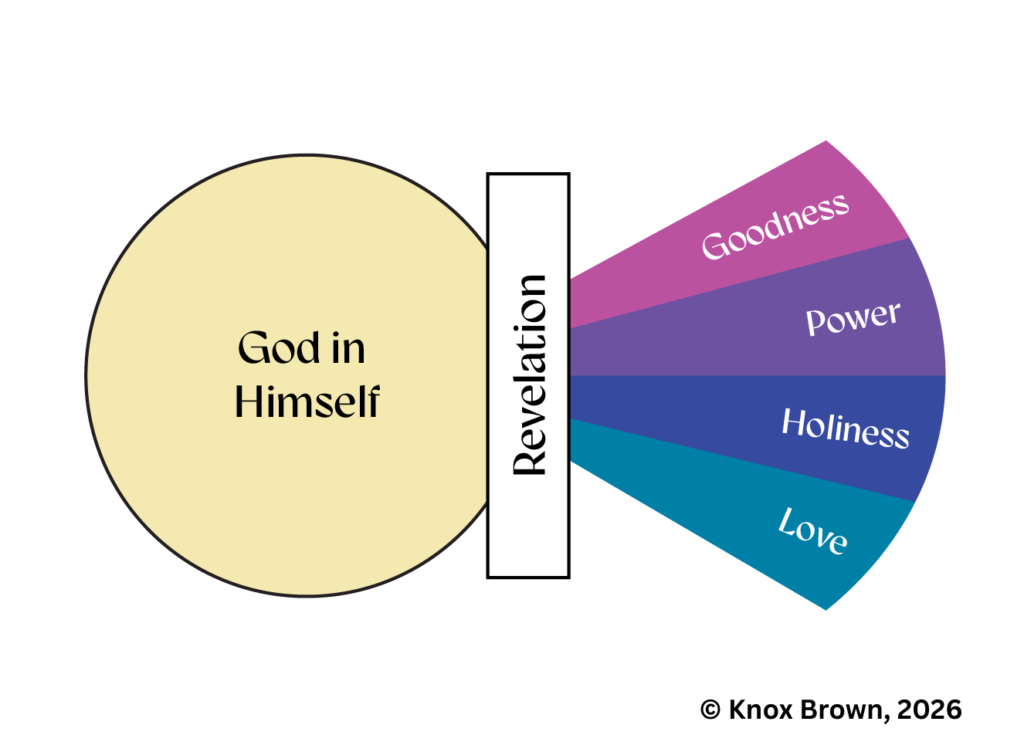

Scripture teaches that God delights in himself: he delights in his glory (Isa. 48:11; Ezek. 39:25), the members of the Trinity delight in one another, and Scripture especially teaches that the Father delights in the Son (John 17:24; Col. 1:13). So God experiences infinite joy, because he is infinite joy. Yet God’s affection, considered in himself, doesn’t stop merely at attributes that correspond to human emotions. Because God acts with his whole being, his affection also encompasses his whole being. This means that if God is holy (and he is), then he experiences holiness as an affection. We don’t think of holiness as an emotion, but there’s a sense where it is in God. Because he is holy, joyful love, he feels holy, joyful love. These affections aren’t different from one another—God doesn’t have one affection of holiness and a separate one of love. Instead, they are different ways of referring to his single undivided affection. Just as God’s being is simple, not made up of parts, so his affection is singular, reflecting all that he is. As in the diagram below, God in himself is without division, but he reveals distinct attributes and affections to us, so that we can know him.

Each attribute God reveals of himself can also be considered as an affection God possesses within himself. God “feels”—that is, he possesses the affection of—All that He Is. What this means is that if we can say that God is something, we can also say that He has eternally felt that very thing. So, in the same way that we ascribe attributes to God, we can ascribe affections to God. Each of God’s revealed attributes—and affections—describes not a quality in God distinct from the others, but a truth about who God is in his simple, undivided nature (God in Himself). And in the same way that we can say that God feels holy, joyful, omnipotent love because he is holy, joyful, and omnipotent love, we can also state the inverse. Because God feels zealous holy love, He is zealous holy love. That’s because God is, inseparably, all that is in Him, and all that is in Him He is. God is identical with His attributes, because He has no parts—He is all that He is. And because God is all that He is actively, He also feels all that He is affectionally. Because God’s being is undivided, his affections are identical with his attributes.1

1. Cf. Joel R. Beeke and Paul M. Smalley, who state that God’s affections “are facets of his eternal, immutable [that is, unchanging] essence.” Beeke and Smalley, Reformed Systematic Theology, vol. 1, Revelation and God (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), 838.

Absolute and Relative Affections

All this is well and good, but Scripture also says that God hates sin. Would we be right in saying that God’s being is the fullness of hatred? Certainly not! How are we to parse the difference?

The key is that some of God’s attributes (and affections) would be true of God whether or not anything else existed, and some only apply to God in relation to something other than himself. Even if he had never created the world, God would still experience love because he still is love. Similarly, in himself God is holy, omnipotent, eternal, and unchanging. Other attributes like wrath, mercy, and grace are secondary to God’s being and are true only of his relationship to other things. For instance, wrath and hatred are God’s holiness considered in relationship to sinful creatures and sin.2 Similarly, mercy and grace are not inherent in God in himself since both express a relationship between God’s goodness and love and undeserving objects.3 Within the Trinity, there are no undeserving objects of God’s love and goodness—he is infinitely worthy of his own love and delight. But when, by virtue of the work of Christ, God makes creatures an object of his own goodness in a way they don’t deserve, that is grace. Theologians therefore refer to attributes like love, holiness, and omnipotence as “primary” or “absolute” divine attributes, because they are true of God’s nature itself, while attributes like wrath and mercy are “secondary” or “relative” divine attributes, because they express a relation between God and creatures.

2. Along these lines, Turretin distinguishes between God’s justice in himself (“universal justice”) which encompasses his holiness and justice, and God’s justice towards creatures (“particular justice”) which is God’s acting justly towards his creatures and is grounded on his just character. Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, trans. George Musgrave Giger, ed. James T. Dennison Jr., vol. 1 (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1992), 234–241.

3. So, Turretin, Institutes, 1:241–244. Likewise, Van Mastricht notes that not only God’s mercy and grace, but also his beneficence (that is, his general goodness towards even apart from sin) can be considered as his goodness-in-relation. Van Mastricht identifies God’s wrath as his goodness in relation. Petrus van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Theology, trans. Todd M. Rester, ed. Joel R. Beeke, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2019), 331–332.

In the same way, some of the emotional language the Bible applies to God is absolute, and some is relative. Just as God’s attributes can be absolute or relative, so his affections are absolute or relative. When John says that the Father loved the Son before the foundation of the world, this is absolute—this affection directly corresponds to an absolute attribute, and is not an expression of that attribute in relation. But God’s compassion and hatred are clearly relative. Within himself, there are none for God to take pity on or be angry with. God’s internal love and goodness, expressed relatively in the attribute of mercy, are also expressed relatively in the affection of compassion. Compassion, like hatred, expresses a relation between God and creatures. But before diving deeper into the relations between God’s affections and his creatures, we need to dig deeper into what God’s affections are, and how they differ from creaturely emotions.

Emotions, Passions, & Affections

What exactly does it mean that God “feels” all that He is? The careful reader will notice that while I’ve consistently referred to God’s affections, I’ve never used the word emotion, even though emotion is a much more common English word. Additionally, when I’ve said that God “feels” something, I frequently put “feels” in scare quotes. Why is that? Well, it’s because God does not experience emotions the way human beings do.

Emotions

“Emotion” is a fairly general and imprecise word in normal conversation. But its technical meaning is as follows:

[An emotion is a] complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements, by which an individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event.4

4. American Psychological Association, “Emotion,” in APA Dictionary of Psychology, accessed February 16, 2026, https://dictionary.apa.org/emotion. Cf. Merriam-Webster, s.v. “emotion,” accessed February 16, 2026, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/emotion. Merriam-Webster defines emotion as “a conscious mental reaction (such as anger or fear) subjectively experienced as strong feeling usually directed toward a specific object and typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body.” This definition raises parallel concerns for the doctrine of God, particularly in its language of “conscious mental reactions” and “subjectively experienced,” which imply passivity and change in the subject.

This definition stresses several factors:

- Emotions are reactions to some stimuli (whether internal or external)

- Emotions are temporary—they involve a change in the person experiencing the emotion,

- Emotions are experienced physically and mentally.

There are serious problems with ascribing these things to God. To start with, he is unchangeable (Mal. 3:6), and emotions involve a change in one’s experience. He is eternal, transcending time, and emotions involve a reaction to things within time. Finally, God is incorporeal (John 4:24); he doesn’t have a physical body, and emotions involve a bodily experience.

Passions

The common denominator in these problems is that emotions involve a passive element. Whenever you or I experience an emotion we are at least partially acted upon, even if only by our own bodies or minds. For this reason, theologians have traditionally called human emotions “passions.” The word passion shares a root with passive, and signifies being acted upon such that the patient (the one experiencing a passion) is somehow conformed or shaped by the passion.5 God does not experience passions. He never receives anything that shapes him or forms him from anyone—not even emotionally. This doctrine is known as divine impassibility: God does not have passions.

5. This definition is adapted from Steven J. Duby, Jesus and the God of Classical Theism: Biblical Christology in Light of the Doctrine of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022), 326. Note that the word patient is also rooted in the word passive.

Affections

Does this mean that God is infinitely apathetic with no concern? Mē genoito (absolutely not)! Scripture uses very emotional language when describing God. Yet when we speak of divine emotions, we are not speaking of passions but of something else—of affections.

In ordinary language, affection and emotion are often used synonymously. But the word affection actually has a technical meaning, which makes it far better for describing God. Affections arise from within the agent, with no conditioning circumstance. Unlike a passion, there is no sense in which an affection is “made to be felt” by another agent, or by an external circumstance. The language of affection highlights that God is active in His own feeling. He is the agent6 who initiates His own emotion—He is not acted upon from the outside, so that an emotion is produced in Him. Instead, He actively wills and produces His own affections. He is the one who purposes all things according to the counsel of His will (Eph. 1:11). Therefore, when we speak of a divine affection, we are speaking of a “transcendent perfection in God” which God feels.7

6. An agent is the opposite of a patient. An agent is one who acts, a patient is one who is acted upon.

7. Anthony Burgess, The Doctrine of Original Sin (London: Abraham Miller for Thomas Underhill, 1658), 338–39, cited in Beeke and Smalley, Revelation and God, 840.

Human emotions are never pure affections. At least insofar as all the emotions we experience are caused by our own changing bodies, we can be understood as passive recipients of every emotion we experience. Creaturely emotions do involve some agency, but none are pure affections with no element of passion.

But God’s affections are not conditioned or caused by anything outside God, nor caused even by changing states within God. Because God has no parts, there is nothing within Him that could change and give rise to a different experience or feeling in His own inner life and being. This means that divine affections are simply God feeling and delighting in all that He Himself is. God is intentionally, actively, and affectively experiencing the fullness of Himself in the very act of being Himself.

Immutability and Biblical Texts that Might Contradict It

This is clearly different from the ways we as human beings experience emotion. We do not feel or experience all of ourselves. Instead, we have the potential to be, act, or feel differently at different times in response to varying stimuli. We have the potential to feel grief, love, sadness, or joy, and certain situations activate some of that latent potential. That change, from the potential to feel something to actually feeling it, is fundamental to human emotion. But God is fully active in all that He is—there is no unrealized potential in Him that could be activated. He is always actively and affectively all He is—He is I AM THAT I AM. And God is all that He is, unchangeably.

All this is straightforward. God is unchanging, and so his affections are unchanging. But doesn’t Scripture ascribe changing emotions to God? Some biblical texts certainly seem to indicate that God’s emotions change relative to creation. For example, Genesis 6:6 says “the LORD regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart.” Scripture also speaks of God’s heart “recoiling” (Hos. 11:8–9), of his “hatred” towards the wicked (Ps. 7:11; 11:5), and of believers’ “grieving” the Holy Spirit (Eph. 4:30). If we were to place grief, wrath, repentance, or anger into God’s eternal being and affections, the result would be devastating. Either we would make God a prisoner to time—having His emotions tossed to and fro by the actions of His creature—or we import these emotions into God’s timeless existence and make Him not the God of eternal blessedness.

In the face of all this, what are we to do? Clearly, theology should not be used to handwave texts like these away. But neither can these texts deny what the whole Bible clearly teaches about the nature of God. A right reading, however, does neither. Rightly understanding God’s affections, far from leading us to dismiss these texts, makes them even weightier.

God’s Affections in Relation

Although texts like these do not indicate that God’s affections change relative to creation or that he experiences passions, they do speak meaningfully about God and our relationship to Him. When we properly interpret these passages in light of God’s simplicity, immutability, and impassibility, we will discover that these texts communicate more, not less.

Per divine simplicity, God is eternally, timelessly acting in all of Himself and feeling all of Himself. That one, timeless act of God being Himself actively, intentionally, and affectively fills all of time and space. God in being God is fully present everywhere at all times without extension. That means that we, as creatures, are always in relation to God—not in relation to some part of God, some aspect of God, but in relation to God as God in all the fullness of all that God is everywhere, inescapably and at every moment of our lives. His presence never decreases, never increases—we are always in relation to the fullness of God.

But the manner in which we are related to God does change. Not because God changes, but because we do—or because we are changed by God. Let’s explore how a right theology of divine affections drives us deeper into these texts, one category at a time. We’ll begin with texts about God’s anger and build towards the most difficult concept—how believers can grieve the Holy Spirit while being in Christ.

God’s Anger

God’s word has much to say about His wrath towards sin. Scripture emphasizes that God hates sin. He does not simply enact wrath as a dispassionate legal consequence—His whole being and affections are involved. For example,

- “His soul hates the wicked” (Ps. 11:5).

- “God is angry with the wicked every day” (Ps. 7:11, NKJV).

- “The LORD avenges and is furious” (Nah. 1:2, NKJV)

God has a burning anger towards sin and sinners. To be a sinner is to be in a relationship with God in which all of his being is hostile to you. We typically think of God’s anger as an emotion arising in God. In that view, God’s anger is terrible, but it is still only a “part” of Him. But the truth is much worse. God’s anger is not a psychological disturbance or a “new emotion.” Rather, anger and wrath describe a relationship in which God, in the fullness of His being, His infinite, eternal, holy, joyful, omnipotent love and delight in Himself is opposed to the object of His wrath.8

8. So Van Mastricht identifies God’s just wrath as his goodness in relation. Van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Theology, 2:388.

Scripture testifies that in God’s anger, His affective life remains one of holy, righteous delight.

Deuteronomy 28:63—And as the Lord took delight in doing you good and multiplying you, so the Lord will take delight in bringing ruin upon you and destroying you.

1 Samuel 2:25—But they would not listen to the voice of their father, for it pleased the Lord to put them to death.

These verses teach that God’s supreme blessedness and delight remain constant even in his expressions of anger. Nonetheless, predicating anger of the relationship between the sinner and God rather than God’s inner psychological state does not lessen the blow—it heightens it! It means that all God is in His burning zealous love for His own goodness—His infinite affection—is hostile to the sinner.9

9. What about Scriptures in which God says “I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked” (Ezek. 33:11) or “He does not afflict from the heart” (Lam. 3:33)? Though these sound contradictory to the point above, these verses actually confirm the thesis that God’s nature is one of infinite happiness and not infinite wrath or grief. On the one hand, Scripture can say that God “delights” in destroying the wicked, because He is always delighting in His own holiness and in relation to the wicked that delight is expressed in wrath. At the same time, Scripture can say that God does not take pleasure in the death of the wicked to clarify that it isn’t the pain and suffering of wicked people that brings God joy—rather, it is the expression of His own perfect character that delights Him.

God’s Repenting or Regretting

Let’s now turn to texts that speak of God repenting or regretting. Examples include:

Genesis 6:6—”And the LORD regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart.”

1 Samuel 15:11—”I regret that I have made Saul king, for he has turned back from following me and has not performed my commandments.”

We best understand each of these passages in its context. What is being described in both cases is not that God’s life of perfect happiness in Himself suddenly filled with pain. Nor is it the case that (as with human repentance) God’s understanding or affection turned out to be skewed, and so he must repent and reorient his heart and mind.

Rather, in each case, what is being described is a change of God’s actions. In Genesis 6, God sets the earth on a radically new course by wiping out all of humanity except Noah and his family. In 1 Samuel 15, God sets Israel on a new course by removing Saul from kingship and selecting David instead. In neither case did God change His mind—He had already prophesied that the King of Israel would be from Judah (Gen. 49:10)—which Saul was not (1 Sam. 9:1–2)—so we know that the plan to raise up Saul and then remove him had been established long before. In neither case did God reorient His heart and mind away from skewed affections toward righteous ones. Rather, the language is used analogically to express that in the same way in which a repentant man radically changes his outward actions, so God radically changes His outward actions. God does not change internally. Nonetheless, as His plan for history unfolds, He makes changes in the creation—sometimes, as in Genesis 6 and 1 Samuel 15, in radical ways.

Far from undermining the sense of the text, understanding divine repentance as a radical change in God’s revealed actions (while remaining a consistent unfolding of his eternal plan) is the most natural and consistent reading of both passages.10 Two texts clarify this:

10. So Duby, Jesus and the God of Classical Theism, 350.

Numbers 23:19—God is not man, that he should lie, or a son of man, that he should change his mind.11 Has he said, and will he not do it? Or has he spoken, and will he not fulfill it?

1 Samuel 15:29—And also the Glory of Israel will not lie or have regret, for he is not a man, that he should have regret.

11. The Hebrew word for “change his mind” is nāḥam, the same as the word “repent,” seen earlier in Genesis 6:6 and 1 Samuel 15:11.

When all these passages are considered together, it’s as if the author is clarifying, “dear reader, when I say that God regretted Saul being king, I want you to know that God does not regret in the same way that mankind regrets. This is an analogy to help you to understand God’s outward actions.”

Grieving the Holy Spirit

In my opinion, the most difficult text to think through in relation to impassibility is Ephesians 4:30: “And do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, by whom you were sealed for the day of redemption.”

What makes this text difficult is that we cannot say that God’s whole being is directed against a person who is redeemed in Christ. But our disobedience as Christians does not introduce sorrow into the divine life or undermine the perfect, unchanging, eternal happiness of God.

We should understand this text along the lines of the texts above about divine regret. Just as a grieved or offended person may withdraw from a relationship, so the Holy Spirit, without ceasing to indwell us, withdraws the tangible manifestation of His presence in order that we might repent.12 What is being described in the Holy Spirit’s being grieved is a change in external action.

12. Duby, Jesus and the God of Classical Theism, 350–51; cf. Johannes Cocceius, S. apostoli Pauli epistola ad Ephesios cum commentario (Leiden: Danielis, Abrahami & Adriani à Gaasbeeck, 1667), 262–63, cited in Duby, 350n100.

God’s Pleasure in Human Beings

One final group of texts is worth mentioning. Some passages speak of God’s being pleased or delighted with human actions (e.g., Ps. 37:23; 147:11; Col. 3:20; Heb. 13:16). While these aren’t as controversial, some incorrectly take these passages to mean that believers’ obedience can increase God’s happiness. But Scripture clearly teaches that we cannot add anything to God (see Rom. 11:35). Nonetheless, God is genuinely pleased with us. In the very act of creating the world, God chose to graciously allow created things to please Him. Out of the overflow of his infinite pleasure in Himself, God created that which reflects Him and allowed those created things to partake in His own pleasure in Himself. So, when God’s creatures reflect Him, they do please Him.13 Not in the sense that they give him more pleasure than He had before, but in the sense that the pleasure God already has in Himself is now in us too.

13. See Beeke and Smalley, 844.

Conclusion: God’s Affections & the Glory of Salvation

When a sinner, formerly under God’s wrath, facing hostility from God in all that He is, is saved by the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, that person, clothed in Jesus’s righteousness, does not merely experience forgiveness. They do not merely experience blessing and mercy from God reluctantly meted out. Instead, the fullness of who God is in all His holy omnipotent zeal and love is directed towards them in love. We don’t just get part of God—all that God is, He is to us and for us. God does not partially love His people and partially hold disdain for them. No, God is always acting in all that He is, and all that God is is directed towards us as a bottomless fountain of joy and love and favor. Why? Because just as it pleased the Lord to pour out his wrath (Deut. 28:63), so “it pleased the Lord to crush” His Son (Isa. 53:10) so that it might please the Lord to save sinners.