In the heart of 18th-century England, John Wesley began ministry with modest means, but as his preaching and hymn writing flourished, so did his income. Initially enjoying his prosperity, one day he purchased pictures to decorate his walls. His conscience was pricked, however, when he noticed a poor chambermaid dressed in inadequate clothing during the harsh winter and realized he had little money left on hand to help her.[1] Under conviction, he capped his lifestyle to enable greater generosity and began to preach a new principle: “Gain all you can, save all you can, and give all you can.”[2] Wesley’s experience highlights a common question facing most Western believers today: How much is too much? Or how can Christians discern the line between self-interest and greed in a world of plenty?

1. Charles Edward White, “Four Lessons on Money from One of the World’s Richest Preachers” Christian History 19 (summer 1988): 24.

2. John Wesley, “The Use of Money” in The Sermons of John Wesley, 1872 edition. Wesley Center Online, Northwest Nazarene University. Accessed August 16, 2025.

The doctrine of vocation calls us to “work heartily, as for the Lord and not for men” (Col. 3:23), yet the Bible consistently warns of the soul-killing snare of “covetousness, which is idolatry” (Col. 3:5). Christians of every era wrestle with such questions, whether at bonus time, vacation planning, or contemplating bigger purchases. Every purchase invites the sober inquiry: Am I honoring Christ or feeding subtle greed?

Distinguishing Sanctified Self-Interest from Greed

Unfortunately, the New Testament offers no simple line or “holy percentage” for lifestyle versus charity. However, the writings of the apostle Paul provide guidance for moral discernment, enabling believers to distinguish sanctified self-interest from sinful greed. Paul’s first-century letters provide a practical rubric for examining motives and choices as we pursue our God-given vocations.

For example, Paul expects every believer, regardless of background or vocation, to work, accumulate, and donate with biblical wisdom. Working to excess or working to the point of neglecting essential aspects of health, family, or spiritual duties is a sign of greed or acquisitiveness.[3] But sometimes, as in Wesley’s case, a Christian morally pursuing a vocation may be surprised by success in the form of abundance of wealth. Other believers may inherit a substantial fortune, receive a large jury award, or find that a lifetime of diligent saving and avoiding debt results in a sizeable estate.[4] Even middle-income Christians who are wealthy by global standards often have to wrestle with how to faithfully manage growing abundance. In these situations, what is the balance between holding on to possessions and selling everything to give to the poor?[5]

3. Other signs of greed in excessive acquisition beyond neglect of God-ordained duties include compromised integrity or a love of money itself (c.f.; 1 Tim. 3:3, 6:10). For a deeper analysis, see Chapter 2 of Paul David Kotter, “Working for the Glory of God: The Distinction Between Greed and Self-Interest in the Life and Letters of the Apostle Paul,” PhD diss., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2015.

4. The possibility of gaining a fortune by winning the lottery is not considered here, as the author considers state lotteries little more than a tax on people who are bad at math.

5. It is unlikely that the special case of the rich young ruler (Mark 10:217–22; Luke 18:18–23) applies universally to all believers. The early church fathers—Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Jerome, and others—did not read the command to sell all possessions as a universal law. Rather, they saw it as a call to radical detachment from wealth and wholehearted allegiance to God. They generally agreed that it is not the possession of wealth itself, but the inordinate love of wealth that is spiritually perilous. The goal of this essay is to help define “inordinate love” for wealth. For a helpful discussion, see Jared Ingle, “Simplicity: Clement’s Stark Conclusions About the Rich Young Ruler,” Patheos, January 16, 2019.

6. Paul commands diligence and generosity, provision for family, and openhanded care for the needy (1 Thess. 4:10–12; 1 Tim. 5:8; Eph. 4:28), while warning the rich not to set their hope on “the uncertainty of riches, but on God, who richly provides us with everything to enjoy” (1 Tim. 6:17–18).

The Pauline Balance Sheet: Possessing Without Sinning

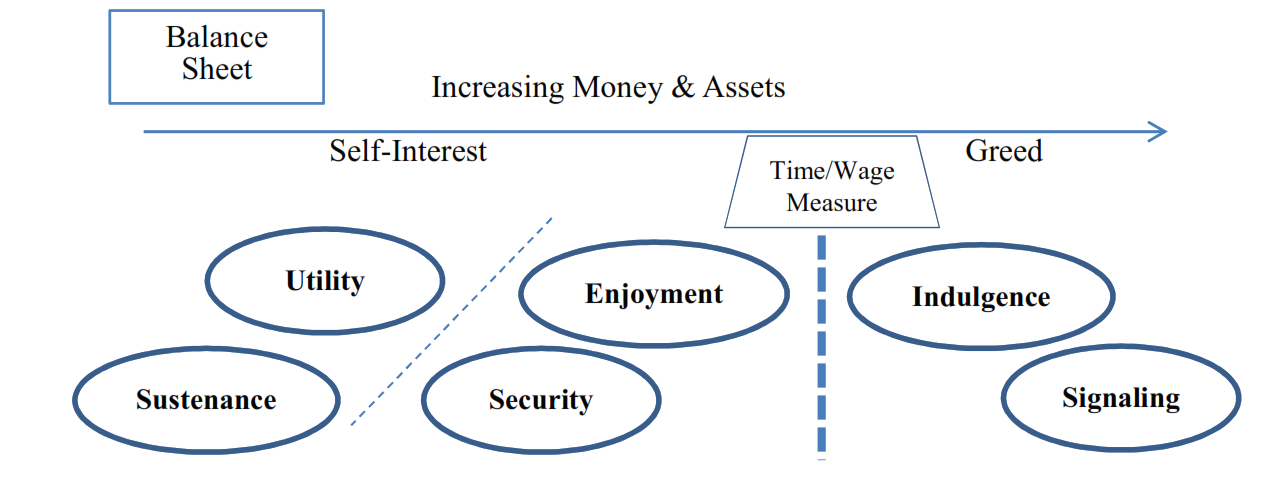

The logic of Paul’s writings invites us to imagine a “balance sheet”—a moral inventory of motivations behind our possessions that helps us align with God’s will. This rubric can help believers evaluate whether our use of possessions reflects sanctified self-interest or slips into sinful avarice. Consider a horizontal spectrum moving from necessities to indulgence and status signaling. On the left, possessions reflect stewardship; on the far right, they reveal self-centered greed. While generosity is always commended in the New Testament, possessions on the left can be kept more comfortably, whereas possessions on the right are an indication of greed.[6]

Pauline Balance Sheet Diagram

Sustenance: Starting on the left, sustenance is the baseline. Paul says believers are expected to maintain whatever possessions are needed to sustain life, providing food, clothing, shelter, and basic care for themselves and their dependents. He wrote, “If anyone does not provide for his relatives, and especially for members of his household, he has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever” (1 Tim. 5:8). God generally provides for our needs through our vocations and expects us to steward those provisions responsibly to sustain ourselves.[7] Greed enters when we use “providing for my family” as an excuse to accumulate far beyond our needs or to hoard out of fear.

7. In 1 Timothy 6:8, Paul sets a minimum bar, not a maximum. We are not generally required to give away every penny beyond literal bread and shirts, though we must keep in mind that the generosity of Christ set a high standard in 2 Corinthians 8:9, “Though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich.”

Utility: Beyond necessities, Paul acknowledged we may possess things that help us fulfill our calling—tools and assets that have productive use. In one of his letters, Paul uses farming imagery: “Who plants a vineyard without eating any of its fruit?” (1 Cor. 9:7). This example is illustrative since a vineyard in the first century was an especially valuable asset that required a substantial capital investment to build a wall, construct a watchtower, and cultivate vines for years before yielding a return. Rather than condemning a “wealthy” vineyard owner holding on to such an asset, Paul understands that such a farmer should benefit from the fruits of that possession. By analogy, quality tools for a tradesman are not indulgences; they are the God-given means to carry out his work. In modern terms, this could be your car (if it enables you to work and serve), your computer, kitchen appliances, or even books and professional clothes. The caution here is to truly use those possessions to increase our capacity to serve and work and not let useful tools multiply into unnecessary gadgets. We should ask about big purchases: Does this asset have real utility for the kingdom, or am I justifying a luxury under the guise of a tool? If it is the former, it likely belongs on the “utility” line of a godly balance sheet.

Security: It is not greedy to save for a rainy day, but rather, it is prudent to save for the losses that inevitably will come in a fallen world. Paul expected that believers would hold some assets in reserve to guard against future crises or foreseen needs (2 Cor. 12:14).[8] He praised the Corinthian church for their generosity in meeting the Jerusalem saints’ famine needs, but he also expected that at another time the reverse might happen—“their abundance may supply your need” (2 Cor. 8:14). This implies each group of believers normally had some surplus stored up “for need.” For instance, having a savings account, some emergency funds, insurance, or reasonable retirement savings can be an expression of wisdom. The subtle difference between prudent planning and greedy hoarding lies in our trust and priorities. Saving becomes hoarding if we stockpile excessive wealth out of fear or pride, all the while ignoring pressing opportunities to bless others.[9]

8. Scripture also commends the ant who stores in summer for winter (Prov. 6:6–8) and wise bridesmaids who had oil in reserve (Matt. 25:1–10).

9. Jesus’s parable of the rich fool (Luke 12:16–21) warns against amassing bigger barns with no view toward God’s kingdom.

Enjoyment: Here we reach an often-overlooked sweet spot: the enjoyment of God’s blessings. Paul affirms that it is legitimate for Christians to have some possessions simply for aesthetic enjoyment, beyond any utility because God “richly provides us with everything to enjoy” (1 Tim. 6:17). This means that after our needs are met, after we have equipped ourselves to work, and after we have saved responsibly, it is not inherently sinful to enjoy some of life’s goodness. This might include having a tastefully decorated home, pursuing a hobby, or occasionally feasting with family. Consider how Paul advised Timothy to counsel the rich: not that they must divest all luxuries, but that they not be arrogant or set their hope on riches, and instead “do good, be rich in good works, be generous and ready to share” (1 Tim. 6:18). In other words, enjoy what God gives you, but hold it loosely and use your wealth to bless others. The danger comes when “simple aesthetic enjoyment” slides into self-indulgence. Paul places a moral boundary here (think of it as the vertical line on the balance sheet diagram). Beyond this line, enjoyment turns to sin. Understanding this distinction leads to the final two categories, which are clear indicators of greed.

Indulgence: When personal enjoyment becomes a dominant pursuit at the expense of spiritual health or love of others, it crosses into indulgence. Paul speaks of those “lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God” in perilous times (2 Tim. 3:4). Self-indulgence means seeking pleasure in a way that harms your soul, neglects the needs of others, or overlooks the cause of Christ. Paul’s example in 1 Timothy 5:6 (NIV) describes a widow who “lives for pleasure” as being spiritually dead. If, like Wesley at the outset of his ministry, we spend so much on ourselves that we can no longer be generous, or if we pamper ourselves to the point of softening our devotion and discipline, we have entered dangerous territory. Paul’s ethic, following Christ’s, always points us toward self-control and sacrifice rather than self-indulgence (Rom. 13:14). “Enjoyment” refreshes us for service and thanks God for a treat. “Indulgence” numbs us to the mission and demands more and more for oneself. In this difficult area of discernment, each of us must honestly assess ourselves and especially invite the opinions and insights of other Christians close to us. We might ask, “If Paul looked at my lifestyle, would he see contentment or soft decadence?” Our goal is not to impress Paul, of course, but to please the Lord, and we know from Scripture that the Lord detests unchecked self-indulgence (Luke 16:19–25; Amos 6:4–7).

Signaling: The final category of greed on Paul’s balance sheet is perhaps the most insidious today: accumulating possessions primarily to display riches or status. Possessions held primarily to make a statement to others about the owner fall under “signaling riches,” and Paul would count this as outright sinful greed. In Paul’s time, people signaled such status through clothing, homes, patronage feasts, and other forms of conspicuous consumption. The gospel strongly opposes such pride. Paul told Timothy that women in the church should dress modestly and not with ostentatious gold or costly attire (1 Tim. 2:9)—a principle that applies to men as well. Signaling riches is the vanity of buying the latest gadget or luxury car not for any functional need or even personal enjoyment, but to advertise one’s success or gain others’ admiration. To combat this, we must cultivate humility and the fear of God, finding our identity in Christ, not in consumer branding. Before any big purchase, a healthy question is: Would I still want this possession if no one else ever knew I had it? By avoiding the trap of signaling riches, we keep our possessions serving us (and God’s purposes) rather than serving our vanity.

Motives and Money: Paul’s Theological Distinction

The six categories presented above are not intended to feed legalism but to cultivate biblical wisdom, guiding faithfulness in an economic reality always vulnerable to loving money. Paul presents sanctified self-interest as pursuing one’s flourishing as God’s steward, not as an end in itself. A thorough analysis of stewardship and greed must go beyond motives to also consider absolute amounts of money, time, and mental focus required to acquire or keep our possessions.[10]

10. For a further analysis of using a time/wage tool to compare relative generosity or greed over long periods of time, see my forthcoming article “The Time/Wage Index: A Framework for Applying Christian Ethical Teachings to Modern Economic Systems” in Symposium: Economic Ethics in Judaism and Early Christianity, Journal of Markets and Morality, (forthcoming, 2025).

How Christians Can Tell if They Are Greedy: Applying the Pauline Balance Sheet

Since greed starts in the heart, these questions are a good place to begin:

- Sustenance: Are your and your family’s needs met with thankful contentment without hoarding?

- Utility: Do your possessions enable faithful vocation and service rather than an assortment of wasteful gadgets or a source of pride?

- Security: Are your savings prudent for the future without replacing trust in God?

- Enjoyment: Do you enjoy God’s gifts gratefully, with generosity and without selfish indulgence?

- Indulgence: Are your expenditures self-focused, dulling spiritual growth and neighborly love?

- Signaling: Do your possessions communicate status, feed pride, or provoke envy rather than humility and gospel witness?

Pastoral Encouragement

Paul calls on Timothy to exhort people like us to “…not be haughty, nor set your hopes on the uncertainty of riches, but on God, who richly provides us with everything to enjoy. They are to do good, to be rich in good works, to be generous and ready to share” (1 Tim. 6:17–18). John Wesley took this admonition to heart, changed his lifestyle, and exhorted his 18th-century audiences to do the same.

Rather than guilt or asceticism, Paul offers freedom—to work diligently, enjoy gratefully, and give generously under Christ’s lordship. The Pauline balance sheet should not be a burden but a rubric of grace for discerning heart motives and aligning our possessions with kingdom living.