The serpent theme spans the entire Bible—from the beginning of Genesis to the end of Revelation.1 Let’s start with what the Bible teaches about the serpent at the story’s beginning. Genesis 3 teaches at least twelve notable truths about the snake.

Here’s a clarifying note about an aspect of this book’s format: I quote the Bible a lot. I do this for two reasons. First, it helps you engage directly with the Bible and not merely indirectly through what I say about the Bible. To help you connect specific God-breathed words with what I am arguing, I italicize portions of direct quotes. Second, it helps you realize, “Wow! The serpent theme is all over the Bible.” It is a prominent theme at the Bible’s bookends (the beginning of Genesis and end of Revelation) and in between.

The Snake Is Deceitful

Now the serpent was more crafty than any other beast of the field that the Lord God had made. (Gen. 3:1)

The grand story does not begin with the deceitful snake in Genesis 3. It begins with God’s creating the heavens and the earth in Genesis 1–2. The story begins with pure goodness. All is right with the world—until the crafty villain enters the scene.

In English, crafty means cunning or deceitful. But crafty in Genesis 3:1 translates a Hebrew word that is neutral on its own. It can be positive (e.g., Prov. 12:16—prudent as opposed to foolish) or negative (e.g., Job 5:12; 15:5). Here the word is initially ambiguous. But when you reread this story in light of the whole story, crafty is an excellent translation. The serpent is the craftiest wild animal. His first strategy is not to devour but to deceive.

The Snake Is a Beast That God Created

Now the serpent was more crafty than any other beast of the field that the Lord God had made. (Gen. 3:1)

God created the snake, so the snake is not God’s equal. God is un-created; the snake is created. Aseity is true only of God—that is, only God exists from himself without depending on anything else for existence.2 Like every other creature, the snake is not independent of God.

The Snake Deceives by Questioning God

And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, “You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.” (Gen. 2:16–17)

He [i.e., the snake] said to the woman, “Did God actually say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree in the garden’?” And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden, but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’” (Gen. 3:1–3)

The snake does not begin by directly contradicting God. He begins by questioning God.

The snake craftily reframes the situation. Instead of emphasizing that Adam and Eve may eat from every tree except one, the snake asks whether they may eat from any tree.

Instead of rebuking the snake, the woman entertains the idea that God is not benevolent and trustworthy. Maybe God made up that rule to limit her pleasure. Her words “neither shall you touch it” may even embellish what God commanded.

The Snake Deceives by Contradicting God

But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not surely die. For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” (Gen. 3:4–5)

After the snake questions God, the snake intensifies his deceitful assault by contradicting God. He lies and blasphemes God as having selfish motives. This serpent sounds like the devil: “When he lies,” explains Jesus, “he speaks out of his own character, for he is a liar and the father of lies” (John 8:44).

Yes, the woman’s eyes will be opened, but not in a good way. She will know evil by becoming evil herself, and thus she will die spiritually. Little does she know in her innocence that this death will start the countdown to her physical death.

The Snake Deceives by Tempting with Worldliness

But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not surely die. For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise . . . (Gen. 3:4–6)

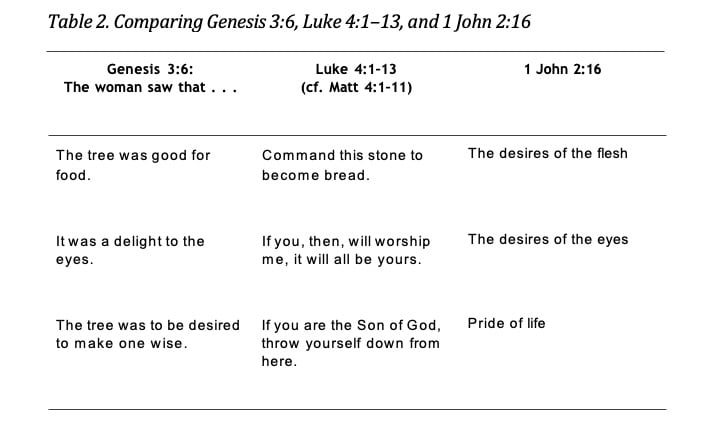

Worldliness is loving the world (see 1 John 2:15–17).3 For us to “love the world” today (1 John 2:15) is to delight in the anti-God culture that permeates this fallen world, to take pleasure in worldly ways of thinking and acting, to take pleasure in what theologian John Frame calls “the bad part of culture.”4 Eve is the first human in history to love the world, and the snake deceives her by tempting her with worldliness—much as Satan later tempts Jesus in the wilderness (see table 2).

I am not certain that the three phrases in 1 John 2:16 line up exactly with Genesis 3:6 and Luke 4 or that John has these parallels in mind. But the three phrases in 1 John 2:16 seem to line up at least roughly with Genesis 3:6 and Luke 4, so the parallel seems legitimate.

The three phrases in 1 John 2:16 are broad and overlapping ways to describe “all that is in the world”:

1. “The desires of the flesh” are whatever your body sinfully craves. A person may crave forbidden food (like Eve did) or excessive food and drink or immoral sex or pornography or security in an idolatrous relationship. Our fundamental problem is not what is “out there” but what is “in here.” It’s not external but internal.

2. “The desires of the eyes” are whatever you sinfully crave when you see it. Basically, this craving is coveting—idolatrously wanting what you don’t have.5 My colleague Joe Rigney tells his sons that coveting is wanting something so bad that it makes you fussy. Eve idolatrously wanted what she didn’t have.

3. “Pride of life” is arrogance produced by your material possessions or accomplishments. Consequently, you may strut around like a peacock, proudly displaying your fashionable clothes or latest gadget or social status. Or you may not be a peacock, yet you still find your security in your raw talents or achievements or savings account. You are proudly independent; you don’t need God. In this case, Eve arrogantly wanted to be independent of God.

One Johannine scholar says of the three phrases in 1 John 2:16, “Translating this as ‘sex, money, and power’ may not miss the mark by much.”6

The Snake Deceives Eve to Rebel against God, and Adam Follows Eve

So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate, and she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate. (Gen. 3:6)

Then the Lord God said to the woman, “What is this that you have done?” The woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.” (Gen. 3:13)

But I am afraid that as the serpent deceived Eve by his cunning, your thoughts will be led astray from a sincere and pure devotion to Christ. (2 Cor. 11:3)

Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. (1 Tim. 2:14)

God commissioned his image bearers to rule over the beasts of the field (Gen. 1:26–27), but his image bearers committed treachery. Instead of obeying the King, they followed the snake.

Eve was not alone. Adam “was with her” (Gen. 3:6). So when Adam ate, he rebelled against God not only by failing to obey what God commanded but also by failing to lead and protect his wife. “Adam should have slain and thus judged the serpent in carrying out the mandate of Gen. 1:28 to ‘rule and subdue,’” explains New Testament scholar G. K. Beale, but instead “the serpent ended up ruling over Adam and Eve by persuading them with deceptive words.”7

When God calls to “the man” and asks, “Where are you [singular]?” (Gen. 3:9), he directly addresses Adam—not both Adam and Eve. Adam is primarily responsible because he is the head of the husband-wife relationship. Thus, later Scripture blames Adam for the fall into sin (Rom. 5:12–21; 1 Cor. 15:21–22).8 He should have killed the dragon and rescued the girl.

As a Result of the Snake’s Deceit, Adam’s and Eve’s Sins Separate Them from God

Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked. And they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves loincloths.

And they heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden. But the Lord God called to the man and said to him, “Where are you?” And he said, “I heard the sound of you in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked, and I hid myself.” He said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten of the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?” The man said, “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit of the tree, and I ate.” Then the Lord God said to the woman, “What is this that you have done?” The woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.” (Gen. 3:7–13)

Adam and Eve’s nakedness symbolized their innocence (see Gen. 2:25), but after they sinned, they clothed themselves because they were no longer innocent (Gen. 3:6). They hid from God because they were ashamed to be in his presence (Gen. 3:8). God gives Adam and Eve the opportunity to confess their sins and take responsibility for them. But they justify themselves by making excuses: Adam blames Eve, and Eve blames the snake (Gen. 3:12–13).

As a Result of the Snake’s Deceit, God Curses the Snake and Promises a Snake Crusher

The Lord God said to the serpent,

“Because you have done this,

cursed are you above all livestock

and above all beasts of the field;

on your belly you shall go,

and dust you shall eat

all the days of your life.

I will put enmity between you and the woman,

and between your offspring and her offspring;

he shall bruise your head,

and you shall bruise his heel.” (Gen. 3:14–15)

God may have originally created the snake with legs and wings—as in our popular picture of dragons. But because of the snake’s deceit, God humiliated the snake by forcing it to slither on its belly in the dust. As a result, now we describe a snake as a reptile that is long, limbless, and without eyelids that moves over the ground on its belly with a flickering tongue, which makes the snake appear to be eating the dust.

God cursed not only the snake but also the snake’s offspring. He cursed them with “enmity” (Gen. 3:15). The rest of the Bible’s storyline traces the ongoing battle between the snake’s offspring and the woman’s offspring. The first seed of the serpent is Cain, who kills his brother Abel (Gen. 4:1–16). The serpent, Jesus explains, “was a murderer from the beginning” (John 8:44), and Cain was the first human murderer. Humans are either children of God or children of the devil (Matt. 13:38–39; John 8:33, 44; Acts 13:10; 1 John 3:8–10).

Instead of continuing through Abel, the seed of the woman continues through Seth: “God has appointed for me another offspring instead of Abel, for Cain killed him” (Gen. 4:25). That line continues through Noah (Gen. 6:9) and then through Abraham,9 Isaac, Jacob, and Judah (Genesis 11–50) and eventually through David all the way to Jesus the Messiah and his followers.101 The woman’s offspring can refer to a group of people (the people of God collectively—cf. Rom. 16:20) and to a particular person (the Messiah—cf. Gal. 3:16).11 Although the serpent will bruise the Messiah’s heel (Jesus dies on a tree), Jesus is the ultimate seed of the woman who will mortally crush the serpent (cf. Gal. 3:16; Heb. 2:14–15; 1 John 3:8). “By going to the cross,” explains New Testament scholar D. A. Carson, “Jesus will ultimately destroy this serpent, this devil, who holds people captive under sin, shame, and guilt. He will crush the serpent’s head by taking their guilt and shame on himself.”12

As a Result of the Snake’s Deceit, God Punishes Eve and Adam

To the woman he said,

“I will surely multiply your pain in

childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth

children.

Your desire shall be contrary to your

husband, but he shall rule over you.”

And to Adam he said,

“Because you have listened to the voice of your wife

and have eaten of the tree

of which I commanded you,

‘You shall not eat of it,’

cursed is the ground because of you;

in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life;

thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you;

and you shall eat the plants of the field.

By the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread,

till you return to the ground,

for out of it you were taken;

for you are dust,

and to dust you shall return.” (Gen. 3:16–19)

God punished Eve and Adam with pain. He punished the woman with pain in childbearing13 and with pain in how she and her husband struggle to lead in a marriage relationship. Instead of gladly following her husband, the woman desires either to dominate him by usurping his leadership or to possessively cling to him by wanting him to be more for her than he can. And instead of responsibly exercising headship by lovingly leading his wife, the man selfishly fails to guide and protect his wife—either by treating his wife in a harsh and domineering manner (Gen. 3:16) or by lazily abdicating primary leadership to his wife (Gen. 3:1–6).

By cursing the ground, God punished the man with pain in cultivating the ground. Adam sinfully ate forbidden food; consequently, it is now more difficult to grow food. God created the earth as abundantly productive, but now he has cursed it.

Further, God punished mankind with mortality. As a result of physical death, humans return to the very ground over which the snake must now slither.

As a Result of the Snake’s Deceit, God Clothes Adam and Eve with Garments of Skin

Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked. And they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves loincloths.

. . . But the Lord God called to the man and said to him, “Where are you?” And he said, “I heard the sound of you in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked, and I hid myself.” He said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten of the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?” . . .

. . . And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife garments of skins and clothed them. (Gen. 3:7, 9–11, 21)

Where did the garments of skin come from? God killed animals to cover the shame and guilt of their sin. This appears to anticipate animal sacrifice under the Mosaic law (cf. Leviticus 1–7) and ultimately the substitutionary sacrifice of Jesus himself (cf. Rom. 3:21–26).

As a Result of the Snake’s Deceit, God Banishes Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden

Then the Lord God said, “Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil. Now, lest he reach out his hand and take also of the tree of life and eat, and live forever—” therefore the Lord God sent him out from the garden of Eden to work the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man, and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim and a flaming sword that turned every way to guard the way to the tree of life. (Gen. 3:22–24)

This part of the story connects to two major themes in the Bible’s storyline.

1. Exile and exodus.14 God banishes sinful people from his special presence (exile), and he redeems his people from exile (exodus). Here are some highlights of this theme that begin in Genesis 3: God exiles Cain to the land of Nod (Genesis 4), delivers Noah from the flood (Genesis 6–9), exiles rebellious people after the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11), brings Abraham out of Ur (Genesis 15), brings his people out of Egypt (Exodus 1–15), exiles the northern kingdom of Israel to Assyria (2 Kings 17) and the southern kingdom of Israel to Babylon (2 Kings 25), and delivers his people from exile in Assyria and Babylon back to the land. The climactic exile is Jesus’s atoning death on the cross (Mark 15:34), and the climactic exodus is Jesus’s resurrection. Now God’s people have entered into rest (Hebrews 3–4) while living as holy pilgrims in exile in this world (1 Pet. 1:17; 2:9–11). In the ultimate exodus, God’s people will forever enjoy God in the new heavens and new earth, and in the ultimate exile, God will forever banish his enemies from his presence.

2. Temple.15 The temple theme begins with the garden of Eden. When God creates the heavens and the earth in Genesis 1–2, the garden of Eden is his dwelling place. God’s dwelling place is associated with heaven, and he “comes down” to earth. The garden of Eden is the first temple, “the temple-garden,” “a divine sanctuary.”16 It’s the place where humans meet with God. There are many parallels between the garden of Eden and the tabernacle/temple. The Most Holy Place or the Holy of Holies in the tabernacle and temple kept the ark of the covenant surrounded by two elaborate, gold cherubim. This room was God’s throne room, and only the high priest entered the Most Holy Place once a year to make atonement for the people. When priests served in the Holy Place, the inner veil kept them from seeing into the Most Holy Place.

God instructed the Israelites to skillfully weave cherubim into the inner veil (Ex. 26:31; cf. 36:35). The Most Holy Place parallels the garden of Eden. After God expelled Adam and Eve from the garden, “He drove out the man, and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim and a flaming sword that turned every way to guard the way to the tree of life” (Gen. 3:24). In a similar way, the cherubim woven into the inner veil symbolized that sinful humans could not enter this temple either.

The temple theme climaxes in Jesus. Jesus, the God-man, “tabernacles” among humans. “The Word became flesh and dwelt [i.e., tabernacled] among us” (John 1:14). His body is the temple (John 2:18–22). And when he died on the cross, the veil between the Holy Place and the Most Holy Place “was torn in two, from top to bottom” (Matt. 27:51). Jesus’s death makes it possible for people to go directly into God’s presence (see Heb. 6:19–20; 10:19–22). The temple rituals and the Mosaic law-covenant are now obsolete. Jesus is our temple, our priest, our sacrifice.17

Now the church is collectively God’s temple (1 Cor. 3:16–17; 2 Cor. 6:14–7:1; Eph. 2:21–22; 1 Pet. 2:4–10). So is the individual Christian’s body (1 Cor. 6:19–20). The ultimate temple is the new Jerusalem (Rev. 21). “And I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb” (Rev. 21:22).

The Snake Is Satan

I want you to be wise as to what is good and innocent as to what is evil [cf. Gen. 3:5]. The God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet. (Rom. 16:19–20)

But I am afraid that as the serpent deceived Eve by his cunning, your thoughts will be led astray from a sincere and pure devotion to Christ. (2 Cor. 11:3)

And another sign appeared in heaven: behold, a great red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns, and on his heads seven diadems. And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him “The accuser of our brothers has been thrown down, who accuses them day and night before our God The devil has come down to you in great wrath, because he knows that his time is short!” (Rev. 12:3, 9, 10, 12)

And he seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years. (Rev. 20:2)

Many commentators on Genesis 3 highlight that the text does not explicitly identify the snake as Satan. Some concede that the New Testament identifies the snake as Satan yet are reluctant to interpret Genesis 3 in that way.18 Some insist that the snake in Genesis 3 is not Satan but instead embodies life, wisdom, and chaos.19 But when we read Genesis 3 in light of the whole Bible, we must identify the snake as Satan.20

The Bible does not specify the precise way Satan and the snake in the garden of Eden relate, but Satan somehow used the physical body of a snake in Eden. He may have transformed himself into a snake-like creature, or he may have entered and influenced one of the existing snakes to accomplish his devious plan. Regardless of the precise means, the Bible presents the story of the talking snake as real history—not as a myth or legend or fable (and the Bible presents Adam and Eve as really existing as the first human beings in history).21

[Taken from The Serpent and the Serpent Slayer by Andy Naselli, Copyright © 2020, pp. 33-47. Used by permission of Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers, Wheaton, IL 60187, www.crossway.org.]

- A logical way to begin studying the serpent theme is to locate all the relevant Bible passages that use various terms for serpent. Laying out that data is a bit technical, so it’s an appendix rather than a chapter: “How Often Does the Bible Explicitly Mention Serpents?” If you are more academically inclined, read the appendix before you read chapter 1. ↩︎

- Cf. John Webster, “Life in and of Himself: Reflections on God’s Aseity,” in Engaging the Doctrine of God: Contemporary Protestant Perspectives, ed. Bruce L. McCormack (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 107–24. ↩︎

- Cf. Andrew David Naselli, “Do Not Love the World: Breaking the Evil Enchantment of Worldliness (A Sermon on 1 John 2:15–17),” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 22, no. 1 (2018): 111–25. ↩︎

- John M. Frame, The Doctrine of the Christian Life, A Theology of Lordship (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2008), 866. Cf. Albert M. Wolters, Creation Regained: Biblical Basics for a Reformational Worldview, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005), 64: “World designates the totality of sin-infected creation. Wherever human sinfulness bends or twists or distorts God’s good creation, there we find the ‘world.’” ↩︎

- John Piper, Future Grace: The Purifying Power of the Promises of God, in The Collected Works of John Piper, ed. David Mathis and Justin Taylor, vol. 4 (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2017), 241: “Covetousness is desiring something so much that you lose your contentment in God. . . . Coveting is desiring anything other than God in a way that betrays a loss of contentment and satisfaction in him. Covetousness is a heart divided between two gods. So Paul calls it idolatry.” Compare the last sentence of 1 John: “Little children, keep yourselves from idols” (1 John 5:21). ↩︎

- D. Moody Smith, First, Second, and Third John, Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox, 1991), 66. Cf. John Piper, Living in the Light: Money, Sex, and Power; Making the Most of Three Dangerous Opportunities (Washington, DC: Good Book, 2016). ↩︎

- G. K. Beale, A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011), 34–35. ↩︎

- Cf. Raymond C. Ortlund Jr., “Male-Female Equality and Male Headship: Genesis 1–3,” in Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, ed. John Piper and Wayne Grudem (Westchester, IL: Crossway, 1991), 107–8. ↩︎

- See James M. Hamilton Jr., “The Seed of the Woman and the Blessing of Abraham,” Tyndale Bulletin 58, no. 2 (2007): 253–73. ↩︎

- See John L. Ronning, “The Curse on the Serpent (Genesis 3:15) in Biblical Theology and Hermeneutics” (PhD diss., Westminster Theological Seminary, 1997); Michael Rydelnik, The Messianic Hope: Is the Hebrew Bible Really Messianic?, New American Commentary Studies in Bible and Theology 9 (Nashville: B&H, 2010), esp. 129–45. ↩︎

- See James M. Hamilton Jr., “The Skull Crushing Seed of the Woman: Inner-Biblical Interpretation of Genesis 3:15,” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 10, no. 2 (2006): 30–55; Jason S. DeRouchie and Jason C. Meyer, “Christ or Family as the ‘Seed’ of Promise? An Evaluation of N. T. Wright on Galatians 3:16,” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 14, no. 3 (2010): 36–48. ↩︎

- D. A. Carson, The God Who Is There: Finding Your Place in God’s Story (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2010), 37. ↩︎

- See Jesse R. Scheumann, “A Biblical Theology of Birth Pain and the Hope of the Messiah” (ThM thesis, Bethlehem College & Seminary, 2014). Scheumann concludes: “As paradoxical as it sounds, birth pain is a redemptive judgment. Judgment is the dominant connotation of the imagery throughout Scripture. But birth pain is redemptive in that the Messiah would come through the line of promise, through birth pain (Gen 3:15–16; 35:16–19; 38:27–29; Mic 4:9–10; 5:2–3[1–2]; Song 8:5; 1 Chr 4:9; Rev 12:2), and he would bear the judgment in birthing the new covenant people (Isa 42:14; Isa 53:10–12; John 16:20–22; Acts 2:24), just as God writhed in birthing creation (Ps 90:2; Prov 8:24–25) and in birthing the old covenant people (Deut 32:18). (115)” ↩︎

- Cf. Iain M. Duguid, “Exile,” in New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, ed. T. Desmond Alexander and Brian S. Rosner (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 475–78; Rikki E. Watts, “Exodus,” in Alexander and Rosner, New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, 478–87; Thomas Richard Wood, “The Regathering of the People of God: An Investigation into the New Testament’s Appropriation of the Old Testament Prophecies concerning the Regathering of Israel” (PhD diss., Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 2006); Alastair J. Roberts and Andrew Wilson, Echoes of Exodus: Tracing Themes of Redemption through Scripture (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2018). ↩︎

- See G. K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God, New Studies in Biblical Theology 17 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004); G. K. Beale and Mitchell Kim, God Dwells among Us: Expanding Eden to the Ends of the Earth (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2014). ↩︎

- T. Desmond Alexander, From Eden to the New Jerusalem: An Introduction to Biblical Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2008), 20–21. ↩︎

- See Timothy Keller, King’s Cross: The Story of the World in the Life of Jesus (New York: Dutton, 2011), 48. ↩︎

- E.g., John H. Walton, Genesis, NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 210; Walton, The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2–3 and the Human Origins Debate (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 128–39. ↩︎

- E.g., Karen Randolph Joines, Serpent Symbolism in the Old Testament: A Linguistic, Archaeological, and Literary Study (Haddonfield, NJ: Haddonfield, 1974), 16–41, esp. 26–27. ↩︎

- Cf. Kenneth A. Mathews, Genesis 1–11:26, New American Commentary 1A (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1996), 234–35. ↩︎

- See James K. Hoffmeier, “Genesis 1–11 as History and Theology,” in Genesis: History, Fiction, or Neither? Three Views on the Bible’s Earliest Chapters, ed. Charles Halton, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2015), 23–58 (also 98–100, 140–49); Wayne Grudem, “Theistic Evolution Undermines Twelve Creation Events and Several Crucial Christian Doctrines,” in Theistic Evolution: A Scientific, Philosophical, and Theological Critique, ed. J. P. Moreland et al. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2017), 783–837; Vern S. Poythress, Interpreting Eden: A Guide to Faithfully Reading and Understanding Genesis 1–3 (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019). ↩︎