It is vital for Christians to understand that there is one gospel. There is one message of Jesus Christ’s redemption that must go out to the world. That message has many components and is so multifaceted that it must be conveyed in various terms, but in the final analysis both Old and New Testaments present one coherent message of salvation. For all the Bible’s diversity, its principal message can be summarized in that word, the “gospel.” A pithy summary goes like this:

The gospel of Jesus Christ is the announcement to the world that the Creator God has planned and brought about in history his purposes of redemption—personal and cosmic—through the birth, ministry, death, resurrection and ascension of his son Jesus Christ. Now all sinners are called to repent and put their trust in and follow Jesus, wherein they receive forgiveness of sins, the gift of the Holy Spirit, inclusion into his international people, and the promises of resurrection and eternal life in a new creation.

It is hard to find any singular passage that expresses all those ideas, but that is the progressive and cumulative message of the Bible. Anything less is a truncated and insufficient definition of the “gospel.” Anything different entirely is a false gospel.

Yet, that term “Gospel” is also the name we give to the first four books of the New Testament. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are all biographies of Jesus Christ that climax in his death and resurrection for the salvation of his people, which is why we call them “Gospels.” They tell that story of how God has climactically worked in history to forgive and save his people through Jesus Christ. Yet, for all their similarities, those four books are fascinatingly different. Each portrays Jesus from a slightly different angle—same Jesus, unique perspective. That is why their proper titles are not “The Gospel of…”, but “The Gospel According to…” For they all tell that selfsame gospel, only with unique storytelling and structural dynamics. It is highly valuable, therefore, to look at each Gospel in its own right and let that author tell us his complete and coherent message, and not pick them apart to deal with the stories and sayings of Jesus in the abstract, or mash them all up into a monotone reading. The best reading of the Gospels is to let each have its unique voice and allow the structure and language of each to operate as whole narratives that can support and interpret themselves, as the authors gave them to the world. To that end, this essay will let Matthew speak. How does his text, as a whole and integrous unit, describe that one gospel?

To answer that question we must look to the details of Matthew itself, and notice the way the author has provided all the necessary linguistic and structural guidance for interpretation. When we give the text of Matthew that sort of controlling power, two critical features stand out: references to the Old Testament in the opening passages, and the careful organization of the material. When we take those features into careful consideration we can see clearly that Matthew’s overall message is that the Lord has finally fulfilled his promises to Abraham and David by inaugurating an eternal kingdom and constructing his end-times temple, only through Jesus’s death and resurrection.

Matthew’s Old Testament Background

It is impossible to overstate the importance of how any piece of art begins. What are the first words? What are the first impressions? These opening words and moments then instruct the reader/audience how to interpret the rest of the work.[1] In Matthew’s case, the book begins by invoking memories of David and Abraham and emphasizing that Jesus is their “son” (Matt. 1:1, 2, 6, 17, 20). The first sentence of the Gospel is, “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Matt. 1:1). This is a startling opening. Is it not a signal to the reader that the rest of this work will reveal how God has finally fulfilled his promises to David and Abraham? Those ancient promises, inhibited by so many struggles throughout Israel’s history, are on the verge of fulfillment! Matthew is basically saying in this opening, “Read on, and find out how!” That means, to understand the Gospel according to Matthew, we must first understand what the Old Testament expectations are concerning David’s and Abraham’s “son”—and what is holding them back.

1. See e.g. Rikki E. Watts, Isaiah’s New Exodus in Mark (BSL; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2000; repr. from WUNT 2/88; Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1997), 53–90; Nicholas G. Piotrowski, Matthew’s New David at the End of Exile: A Socio-Rhetorical Study of Scriptural Quotations (NovTSup 170; Leiden: Brill, 2016), 18‒31.

We begin with Abraham. In Genesis 12:1‒3 we read this:

1 Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. 3 I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

These are the Lord’s first words to Abraham. Notice three elements here:

- Abraham is promised a land (Gen. 12:1).

- Abraham is promised a great nation (Gen. 12:2).

- Abraham will both be blessed, and be a blessing to the whole world (Gen. 12:2–3).

No sooner do these promises begin to be realized, however, that Abraham is told to sacrifice his one and only heir in Genesis 22. Yet, as Abraham raises the knife over Isaac, the Lord suddenly provides a ram to offer up “as a burnt offering instead of his son” (Gen. 22:13). Upon this act of obedience the Lord functionally repeats his promises of Genesis 12:1–3 (in Gen. 22:17–18). In turn, this episode with Abraham’s “son”—a word emphasized eleven times in Genesis 22—becomes the paradigm for Israel’s entire sacrificial system. Furthermore, the story of Abraham’s son in Genesis 22 also carries a resurrection “on the third day” typology (Gen. 22:4; see esp. Heb. 11:9).[2] The upshot of all this is to understand that the “son of Abraham” in Matthew 1:1 bears connotations of sacrifice and resurrection in order to bring the “blessing” of Genesis 12:3 to “all the families of the earth.”

2. Stephen G. Dempster, “From Slight Peg to Cornerstone to Capstone: The Resurrection of Christ on ‘The Third Day’ According to the Scriptures,” WTJ 76.2 (2014): 379–80, 387–88.

Considering now “the son of David,” 2 Samuel 7 is the place to look. The chapter begins as David has “rest” in the land (2 Sam. 7:1), a partial fulfillment of those Genesis 12 promises. Then in 2 Samuel 7:12‒14a the Lord tells David,

12 “When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. 13 He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. 14a I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son.”

Here we see some very similar promises that we saw with Abraham, only more particular. David’s son will:

- Build the temple of the Lord (2 Sam. 7:13).

- Receive a kingdom that never ends (2 Sam. 7:13).

Henceforward that great nation from Genesis 12 will become a kingdom, and David’s son will rule as king over it. And the building of the temple will be the crowning achievement of this kingdom, for it is the means by which God graciously dwells among his people.[3] Thus, the promises to David are a particularization and amplification of the promises to Abraham, now running through the House of David.

3. As Nicholas Perrin puts it, “The main significance of this land [lies] in the fact that it would contain Yahweh’s dwelling” (The Kingdom of God: A Biblical Theology [BTL; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019], 49).

Immediately following David on the throne was Solomon. He too has rest in the land and reigns over a great kingdom all the days of his life. As David’s son, Solomon also builds the temple of the Lord (1 Kings 5–7). Surely this is the highwater mark of the Old Testament as all the promises of Genesis 12 are realized, God dwells among his people, and all the surrounding nations are blessed (1 Kings 8).[4] Yet, this Solomonic kingdom does not last “forever.” For the House of David—the subsequent kings after Solomon—slides into exile, and the Old Testament ends with a question mark over God’s promises to both Abraham and David. Will there be a new son of David who rules over God’s people in the land? Will this new son of David build a temple for the Lord? Will the son of Abraham bring blessing to all the families of the earth? And if so, how?

4. See Graeme Goldsworthy, Christ-Centered Biblical Theology: Hermeneutical Foundations and Principles (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2012), 111–32.

By starting his Gospel account with a genealogy of Jesus Christ who is called “the son of David, the son of Abraham,” Matthew builds anticipation around these ancient promises. They had an initial fulfillment in David and Solomon’s kingdom, but for hundreds of years they have laid dormant. And it seems to be that Matthew is indicating that “the deportation to Babylon” (Matt. 1:11–12, 17) is the historical barrier that has blocked up those promises.[5] Now, Matthew stimulates the reader with just the first sentence: get ready for the full realization of these promises.

5. Nicholas G. Piotrowski, “‘After the Deportation’: Observations in Matthew’s Apocalyptic Genealogy,” BBR 25.2 (2015): 192–98.

This is important for reading the first Gospel because now we are clued in to what Matthew thinks he is accomplishing with his gospel account. Matthew’s biography of Jesus is not a collection of stories of what Jesus did and said written merely so we can know the factoids of Jesus’s life. Rather, the very reason for writing this biography is because the collective effect of what Jesus did and said is to bring God’s purposes through Abraham and David to completion. This realization turns on our reading antenna to perceive critical Abrahamic and Davidic sonship emphases throughout the rest of Matthew.[6]

6. Leroy Andrew Huizenga, “Matt. 1:1: ‘Son of Abraham’ as Christological Category,” HBT 30 (2008): 103–13.

Again, those emphases and expectations are that the “son” of David and Abraham will:

- Bless all the peoples of the earth.

- Reign over an eternal kingdom.

- Establish a kingdom through substitutionary sacrifice and resurrection.

- Build the temple of the Lord.

We will see below how Matthew capitalizes on these massive Old Testament hopes to describe how Jesus brings the Kingdom of Heaven to Israel and all nations.

Matthew’s Structure and Discourse

In addition to this invocation of Old Testament hopes in his first sentence, Matthew also provides helpful structural cues. In Matthew 4:17 and 16:21 this phrase gets repeated: “From that time Jesus began to . . .” Specifically, these verses read,

4:17 From that time Jesus began to preach, saying, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.”

16:21 From that time Jesus began to show his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised.

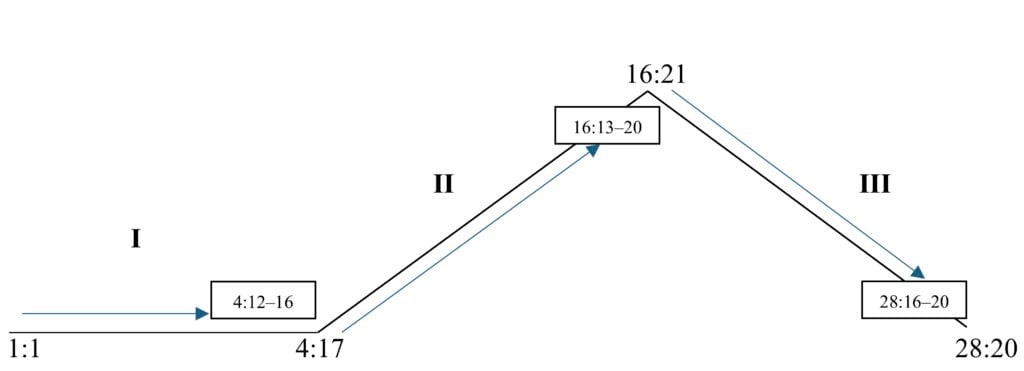

This repetition is not coincidental. These are seams in the Gospel that divides its content into three conceptual blocks.[7]

7. See Jack Dean Kingsbury, “The Structure of Matthew’s Gospel and His Concept of Salvation-History,” CBQ 35 (1972): 453‒66.

- Block I Matthew 1:1‒4:16

- Block II Matthew 4:17‒16:20

- Block III Matthew 16:21‒28:20

The first block provides the theological context for all that ensues. And what Jesus begins to do at those seam verses, Matthew 4:17 and 16:21, contextualizes the specific episodes in the subsequent blocks of text. Then the climax of each block opens the door to the next block.[8] A visual depiction of Matthew’s structure and discourse, therefore, would look like this:

8. To be sure, many outlines of Matthew have been proposed, and most have a more detailed organization of the material than just three major blocks. But they must at least take these seems verses into account and incorporate them somehow, even in a more detailed outline.

I have already commented above how Block I opens with a very strong invocation of Davidic and Abrahamic expectations. Throughout the rest of this block Matthew places seven direct Old Testament quotations, which is a very high concentration compared to the rest of the Gospel. Each of them comes from contexts that deal with Israel’s end-times vision for the re-enthronement of the House of David and/or their hopes for return from exile.[9] Taken together, the quotations anticipate that the son of David will resolve the exile and open the door to the rest of God’s promises. The last quotation especially rings that bell. This is where we find the famous quote of Isaiah 9. Matthew 4:15‒16 reads,

9. Piotrowski, Matthew’s New David, esp. 227‒36.

15 The land of Zebulun and the land of Naphtali,

the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles—

16 the people dwelling in darkness

have seen a great light,

and for those dwelling in the region and shadow of death,

on them a light has dawned.

The language of “the way of the sea” and light in the darkness are Isaianic images for the end of the exile.[10] And in the broader context of Isaiah, this “way” will be opened and the light will shine when the “child is born” to inherit “the throne of David” (Isa. 9:6‒7). Thus, Matthew’s final Old Testament quotation in his prologue invokes the hope that the House of David will end Israel’s exile—that great calamity of the Old Testament that is blocking the Abrahamic and Davidic promises of God.

10. Piotrowski, Matthew’s New David, 205‒11.

It is with that that Block II begins: “From that time Jesus began to preach, saying, ‘Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand’” (Matt. 4:17). The conclusion to be drawn here is that Jesus’s preaching ministry is that end-of-exile light now shining into history.[11] Thus, the barrier that has long damned up the promises of God is now receding in the life and ministry of Jesus Christ.

11. Piotrowski, Matthew’s New David, 215–17.

In Block II, therefore, according to Matthew 4:17, the principle focus is Jesus’s preaching. In this block of text we have the famous sermon on the mount, missionary discourse, teaching on the sabbath, parables, and Jesus’s query of Peter regarding who he is. The astute observer, however, will quickly point out that this section is not only preaching, but also filled with miracles: the healing of many people, casting out demons, controlling nature, and multiplying the fish and loaves on two occasions. The value of noticing the seam in Matthew 4:17 is understanding that Jesus’s preaching leads the way, and those miracles are therefore related to the preaching. That is, the miracles are not set in the abstract, as though they are raw demonstrations of Jesus’s power. Rather, they are part of Jesus’s preaching ministry, and they find their meaning therefore in relation to the content of Jesus’s preaching.

And that content, according to Matthew 4:17, is about the kingdom of heaven and the need to repent. We can take a step further, therefore, and say that the preaching (and related miracles) in this section are aimed at explaining all things concerning the kingdom and what people’s response ought to be—namely, the nearness of the kingdom, the nature of the kingdom, the inevitable spread of the kingdom, the ethic of the kingdom, who is the king of the kingdom, and so forth. Our reaction to such is simple. In light of all this, Jesus says “follow me” (Matt. 4:18‒25).

It all leads to the climactic episode at the end of Block II in Matthew 16:13–20. For brevity’s sake and to keep with the structural focus of this essay, we will only look at Peter’s identification of Jesus as “the Christ,” and Jesus’s identification of Peter as “the rock” on which he builds his church.

Jesus’s question in Matthew 16:13, “Who do people say the Son of Man is?” is the capstone question for Block II. After all his preaching of the kingdom, and concomitant miracles, it is time to clearly identify for the reader who this Jesus is. By calling him “the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matt. 16:16) Peter proclaims Jesus as the heir to the House of David. This is clear for several reasons, but we can point out just one: “the Son of God” is the term arising from 2 Samuel 7:14 as a moniker for David’s lineage.[12] Thus, Peter has accurately identified Jesus as the genealogy already has—this is the one who will reverse the exile and bring all the promises to the House of David to bear. As we saw above, that means inaugurating an eternal kingdom and building the temple of God. On that first point we see, therefore, that Jesus’s preaching ministry has been effective: Peter has made the connection from Jesus’s preaching that the kingdom is nigh, and Jesus, the one that is in the line of David, must be its King.

12. R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 618–19. In other contexts “Son of God” means the second person of the Trinity (e g. John 17:1; Romans 1:3), but here it means the earthly king to rule Israel and the nations. Context tells which one any New Testament author has in view at any time.

But what about that related expectation that this same Davidic son will build God’s temple, the special place where God dwells among his people? This is the first bullet point on the messianic job description per 2 Samuel 7:13.[13] Well, right on cue after Peter decisively identifies Jesus as this Davidic “son,” Jesus goes on to call Peter “the rock” and then talk about what he will build on this rock. The reader anticipates that he will say “I will build my temple.”[14] That Jesus says “I will build my church” powerfully identifies his community of followers as the new covenant theological equivalent of Israel’s old covenant temple![15] This is an awesome claim, because as we have seen, Matthew is all about creating expectations. Thus, now that Jesus is clearly identified as the Davidic King, and because he has continually announced the arrival of David’s kingdom in his preaching (and affiliated miracles), two promises then remain for the rest of the book: that this kingdom will remain forever and that Jesus will build a community of people who fill the theological role of Israel’s Old Testament temple, the dwelling place of God.

13. See Donna Runnalls, “The King as Temple Builder: A Messianic Typology,” in Spirit within Structure: Essays in Honor of George Johnston on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (ed. E. J. Furcha; Allison Park, PA: Pickwick, 1983), 18‒26.

14. Michael Barber, “Jesus as the Davidic Temple Builder and Peter’s Priestly Role in Matthew 16:1–19,” JBL 132.4 (2013): 939–42.

15. This is, of course, an idea that both the apostles Paul and Peter equally capitalize on in their letters.

To sum up Block II, the material in Matthew 4:17‒16:20 is focused on Jesus’s preaching, and specifically his preaching about the kingdom and the response it calls for. This is forecasted for the reader by the structural seam at Matthew 4:17—“From that time Jesus began to preach, saying, ‘Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.’” The block ends with specific Davidic language and the promise that Jesus will build his end-times temple as the church.

In turn, it is vital to see that after this climactic dialogue that Block III immediately begins with Jesus announcing his death and resurrection for the first time in Matthew 16:21. Now that we know Jesus is the eternal King in the line of David, we know who Jesus is. Now what must he do to bring this kingdom to earth and raise his temple?

Opening Block III, the seam verse Matthew16:21 employs the operative verb “show.” Thus, the rest of the Gospel is now a demonstration. To be sure, Jesus still preaches and performs miracles, but judging by Matthew 16:21 it is all designed to show one thing: that he must be killed, and on the third day be raised. In this section we have the famous transfiguration, two more explicit predictions of his death and resurrection, teachings about smaller acts of self-sacrifice, and most of it takes place during Jesus’s passion week. Thus, after Matthew 16:21 the movement of the story is straight to the cross and empty tomb.

This is critical for the same reason as above: it orients our reading of the details and keeps us on the same train of thought as the text. Taking these two blocks together now, we draw this very important conclusion: the kingdom about which Jesus preached and the temple he promises only come into existence through his death and resurrection. And in this too his people must be ready to “follow” him (Matt. 16:24). Thus, Blocks II and III work together to emphasize the what of Jesus’s ministry (Davidic kingdom) and the how (through the true death and resurrection of Abraham’s son). Again, this is helpful because there is so much material in Matthew that is it easy to major on the minors and miss how it all works together. The Gospel is not a disassociated collection of sayings and factoids of Jesus’s life, but it is a specifically organized narrative for understanding this thing called the kingdom of heaven and the requisite manner in which it must come about.

The climax of Block III, Matthew 28:16–20, pulls it all together. What is the result of the kingdom inaugurated by death and resurrection? The answer is that now “all authority in heaven and earth” belongs to Jesus! His kingdom is not over any limited territory, but over all creation! Therefore, Jesus sends his disciples out to all nations to instruct them in the things he preached and showed them, and baptize them into his new community. As such, each convert the apostles win to Christ becomes another stone in the internationally expanding temple of God. This is why Jesus receives worship in this setting (Matt. 28:17) and promises to always be with his people (Matt. 28:20), for these are divine actions in the temple!

To summarize what we have seen, the very first sentence of Matthew invokes the Old Testament hopes and dreams surrounding the promises to David’s and Abraham’s “son.” As such, that means a substitutionary sacrifice and resurrection (“son of Abraham”) will be the means to inaugurating the everlasting kingdom and temple (“son of David”). The prologue of Matthew 1:1–4:16, which I have called Block I, continues to build this anticipation by citing more Old Testament material that promises an end to Israel’s exile, the very barrier that had inhibited the Abrahamic and Davidic promises of God so far. Therefore in Block II, Matthew 4:17–16:20, Jesus preaches about the kingdom of David and provocatively promises that in his role of building the temple of God he will build his church! In Block III then, Matthew 16:21–28:20, Jesus shows his disciples how this kingdom comes only through his substitutionary death and resurrection, to the end that he now has all authority forever now to build up his temple-church with the peoples from all nations.

Matthew’s Overall Message

One particular boast the Lord makes in the Old Testament is that he is able to save, for he exercises sovereign control over all time and space; the false gods of the nations can do nothing of the sort (e.g. Isa. 46:1–11). The Gospel according to Matthew is a powerful literary demonstration of this truth! The promises of God through Abraham and David had hit the hard barrier of exile. It has become the dam through which God’s purposes of redemption could not flow. And so remained the situation for hundreds of years. But now, with the birth of Jesus Christ, the end of the exile has come. As Abraham’s and David’s son, Jesus is the long awaited heir to all the promises of God. In the Gospel according to Matthew we see, therefore, how the kingdom promised to David has finally dawned. And we see in Jesus’s resurrection how such a kingdom can be eternal. Indeed, Jesus’s authority extends over all space—“all authority and heaven and earth has been given to me”—and because he lives forever, his kingdom therefore has no end—“I am with you always” (Matt. 28:18, 20). Moreover, Jesus does not say that he has authority to rule his kingdom only in the land, but as expected from Genesis 12:3, that kingdom stretches as a blessing to all peoples. And because the Great Commission involves bringing those peoples into the fold of his followers—the church—missions is therefore the means through which Jesus is constructing the great son-of-David-built temple, the international dwelling place of God. All of this is accomplished only through his sacrifice and resurrection. Thus, the great expectations through David’s and Abraham’s son have exploded onto the stage of history: a blessing for the people all over the world, an eternal kingdom, a temple for God’s dwelling, all through sacrifice and resurrection. More concisely, the Lord has finally fulfilled his promises to Abraham and David by inaugurating an eternal kingdom and constructing his end-times temple through Jesus’s death and resurrection. Because he is raised, he can raise the temple in himself.[16]

16. Especially helpful, see Edmund P. Clowney, The Final Temple, WTJ 35.2 (1973): 156–89.

It is good that there is only one gospel message. It creates clarity. If there were multiple gospels how would we know where to put our confidence? But because there is one gospel, the way of salvation is straightforward and clear. And it is also good that there are four Gospel accounts. There are four carefully and beautifully constructed narratives that bring us into the life and ministry of Jesus—and quintessentially his climactic cross and resurrection—to experience the saving work of God in dynamic ways. Matthew’s contribution to that end is a breathtaking tour of kingdom and temple through sacrifice and resurrection.