Fatherlessness is an epidemic of western civilization. The downstream effect on western culture is already the subject of several Christ Over All articles. This article is going to move upstream from the social effect of fatherlessness into something far more sublime—the classical Christian doctrine of God.[1]

1. Material for this essay is drawn largely from previous publications by the author and used with permission. See “Theological Language and the Fatherhood of God: An Exegetical and Dogmatic Account,” Eikon 5, no. 2 (Fall, 2023): 46–77; “On the Improper Use of Proper Speech: A Response to Ronald W. Pierce and Erin M. Heim, ‘Biblical Images of God as Mother and Spiritual Formation,’” Eikon 5, no. 1 (Spring, 2023):69–77; Fatherhood for the Glory of God (The Mentoring Project, 2024).

There is a trend in Christian theology, growing in its influence in evangelical spaces, that threatens to move the cultural epidemic of fatherlessness right up into theology proper—into the doctrine of God himself. Many egalitarian evangelical voices have embraced the claim, long advanced by more radical feminists, that the overwhelming preponderance of masculine language for God in Scripture and the history of Christian theology is a serious problem in need of a corrective solution.[2] Post-Christian feminists and liberal Christian feminists are inclined to replace masculine names and titles with feminine or gender-neutral ones. Evangelical egalitarians are more inclined to supplement masculine names with feminine ones in an effort to give equal representation to feminine language in our naming of God. For the egalitarian, just as male and female roles are interchangeable in society, so masculine and feminine divine names are interchangeable in the doctrine of God. At the center of this controversy is the cherished divine name, Father, which many claim is interchangeable with the name Mother. It is now more commonplace than ever before, in more traditional Christian contexts than ever before, to hear prayers offered to “our Mother in heaven” or perhaps “our Mother and Father in heaven.”

2. Some progressive feminists, such as Elizabeth Johnson, deny a strong evangelical doctrine of Scripture as they seek to introduce feminine language into the doctrine of God. See She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse (New York: Crossroad, 1992). Today, Evangelical egalitarians, while claiming to uphold a high view of Scripture as inspired and inerrant, make the case that the preponderance of masculine language for God in Scripture and Christian tradition can and should be corrected with a balancing of gender language for God. See Amy Peeler, Women and the Gender of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2022) and Spencer Miles Boersma, The Father and the Feminine: Exploring the Grammar of God and Gender (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2024).

The replacement of Father with Mother is not merely a matter of semantics. If Father is a revealed proper name of God, as this essay will demonstrate, then this move borders on the blasphemous, as it presumes a prerogative in divine naming that God reserves for himself. It places the creature in the dangerous position of repudiating or diminishing the verity and significance of the very name of God, a name which must not be taken in vain. With respect to both personal and corporate devotion and prayer, addressing God as “Mother” replaces the specifically revealed designation by which the Lord Jesus taught us to address God with a designation nowhere given in Scripture. Furthermore, the move toward a more inclusive or feminine naming of God can have disastrous effects on one’s understanding and application of the divinely appointed calling and position of both fathers and mothers in the home. If there is any legitimate sense in which a human father uniquely ought to pattern his love and leadership for his family after the fatherly care of God for his covenant people, then replacing the name “Father” with “Mother” will result in confusion at best, fatherly abdication and motherly usurpation at worst. This is a serious matter indeed.

Foundational to the argument that Mother is interchangeable with Father as a way of referring to God is the claim that the name Father is a metaphor drawn from the human family. In this article I will argue that the name Father is not, in fact, metaphorical. Rather, Father is a proper divine name predicated of God in two distinct ways, essential and personal. A right understanding of this fact will equip Christians to be faithful in their understanding and application of the analogical relationship between the fatherhood of God and human fatherhood.

The argument will proceed in five steps. First, I will show that God’s names are the result of divine revelation, not human imagination. Next, the nature of all theological language as analogical will be considered. Third, the distinction between proper and figurative speech about God will be discussed. It will be seen that Father is proper, not figurative. The fourth section will take up the important distinction between essential and personal divine names in order to show that Father is predicated of God in both ways in Scripture. In the final section, I will draw on the theological account of Father as a divine name developed in this essay to suggest some limited points of analogical correspondence between divine and human fatherhood.

God’s Names as Divinely Revealed

Reformed theologians have always given significant attention to the biblically revealed names of God. For them, the word “name” is typically reserved for a proper predication that functions as the object of direct address or as the subject of a sentence.[3] In other words, something is a name of God if God is addressed by it in Scripture (e.g., “O LORD, our LORD, how majestic is your name”) or if it is used in Scripture as the subject of a sentence in which God is described by some attribute (e.g., “God is great.”). In standard Reformed nomenclature, these features distinguish a name from more abstract predications, such as divine attributes or eternal trinitarian relations. It is not as though Reformed thinkers ignored such issues as attributes and trinitarian relations in their theology. Far from it, the Reformed Orthodox are known for their robust treatment of such themes. But as Richard Muller observes in his magisterial Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, “From the time of Zwingli onward . . . the names of God provided the Reformed with a primary source and focus” for theology proper as a whole. He goes on to suggest that the reason for this move is a “fundamental biblicism”[4] and a conviction that the divine names offer a primary exegetical pathway into theology proper as a dogmatic locus.[5] Seventeenth-century Dutch Reformed theologian Petrus Van Mastricht, for example, offers an extensive treatise on the divine names and the relationship of names to the rest of the doctrine of God. He says, “The nature of God is made known to us by his names.” He goes on to explain that the names of God (1) reveal the divine essence, (2) distinguish the true God from false gods and creatures, and (3) disclose his properties (attributes and eternal triune relations).[6]

3. For medieval scholastics like Thomas Aquinas, the category of divine names referred to any predication made of God in any way. Thus, all distinctions between different kinds of speech about God are made under the heading: “The Names of God.” See Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, q. 13, “The Names of God.”

4. Of late, the term biblicism has taken on a negative connotation, often being used to refer to a naïve reading of Scripture uninformed by the insights of the orthodox Christian exegetical and dogmatic heritage. Muller does not use the term in this way. Muller understands that the Reformed Orthodox theologians were very conversant with the key Christian voices from the past, drawing heavily on tradition as a guard and guide in their own understanding and exposition of holy Scripture. Muller is using the term to describe the commitment the Reformed had to the utterly unique authority of Scripture as the norma normans (ruling rule) over against Christian tradition as a norma normata (ruled rule). Rhyne Putman addresses the unfortunate connotation of the term biblicism and uses the term “naïve biblicism” to differentiate the two senses with which the term can be used today. See “Baptists, Sola Scriptura, and the Place of Christian Tradition” in Baptists and the Christian Tradition, ed. Matthew Y. Emerson, Christopher W. Morgan, and R. Lucas Stamps [Nashville: B&H Academic, 2020], 27–54.

5. Richard Muller, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics: The Rise and Development of Reformed Orthodoxy, ca. 1520–1725, Vol. 3: The Divine Essence and Attributes (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2003), 246.

6. Petrus Van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Divinity, Vol. 2: Faith in the Triune God, ed. Joel R. Beeke, trans. Todd M. Rester (Grand Rapids, MI: RHB, 2019), 97–98. Later he says, “In the calling of God by names, his attributes come forth” (116).

In Scripture, divine names are either revealed directly by God or are evoked as a response to his revelation. The paradigmatic passage for understanding this truth is Exodus 3:1–15, the historical narrative of the call of Moses at the burning bush. Here it is abundantly clear that the act of naming the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is a divine prerogative. Moses asks God his name, and God answers,

“I AM who I AM.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I AM has sent me to you.’” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘The LORD [YHWH], the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.” (Exod. 3:14–15)

Moses could not choose a name for God based on some mere metaphorical association drawn from the creaturely realm, nor based on his own reason, preference, or imagination. If Moses would know the name of God, it would have to be made known to him by revelation from God. “What is your name?” says Moses. “This is my name,” says the LORD.

At times, God’s disclosure of his name is slightly less direct but no less revealed. For example, In Genesis 16:13, Hagar calls the name of the LORD “You are a God of seeing” (El Roi). There is no account of Hagar asking God his name, nor any indication that the LORD said to Hagar, “This is my name: El Roi.” Nevertheless, Hagar’s naming of God is in response to God’s revelation of himself. Hagar fled from the presence of Abram and Sarai and was desperate and alone in the wilderness where she believed that she and the child in her womb would surely perish. It is then that the LORD “found her” and spoke to her words of promise and instruction. She would bear a son who would live and flourish, and she should return to Sarai and bear the son for Abram. Note that the LORD found Hagar, not the other way around. The name by which Hagar referred to God—“God of seeing”—was a response to his revelation of himself. Thus, Herman Bavinck was right when he said, “We do not name God; he names himself,”—a sentiment Bavinck further clarified by saying, “What God reveals of himself is expressed and conveyed in specific names. To his creatures he grants the privilege of naming and addressing him on the basis of, and in keeping with, his revelation.”[7]

7. Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 2: God and Creation, ed. John Bolt, trans. John Vriend (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2004), 98–99.

In Scripture, names are given by one with authority to one under authority. Recognition of this important feature of names in Scripture shows us the solemnity of the fact that God is the one who reveals his names—we never name him on our own initiative. For example, in Genesis 1:26, God (the one with authority) names mankind (the one under authority) Adam, a name designating both the genus of humanity and the specific name of the first male human created. Adam, who is given dominion over the animals on the earth, names the animals (Gen. 2:19–20). Significantly, Adam also names the woman as a particular type of human (Gen. 2:23) and later gives his wife the specific name, Eve (Gen. 3:20). Furthermore, parents, who have authority over their children, give names to their children, who are to honor and obey their parents (Exod. 20:12, Eph. 6:1). The implication is clear. Only God can name himself because no one and nothing else can ever have authority over God. When creatures presume to choose for themselves new names for God, names which he has not revealed, they are assuming a posture of authority over God rather than one of joyful and humble submission.

While a full survey of divine names is beyond the scope of this essay, there are a few important distinctions in the way that Scripture predicates names of God that merit careful attention as we seek to understand Father as a divine name.

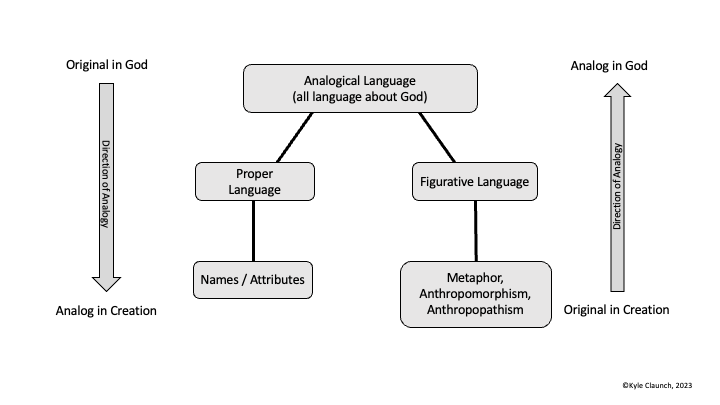

Analogical Language in Speech about God

All creaturely language about God is analogical, including the language God himself uses in holy Scripture. This, however, is not the same thing as saying that all creaturely language about God is metaphorical. To say that all language about God is analogical is to recognize two facts. First, God has chosen to reveal himself truly to creatures in a way that can be understood by creatures, namely through created words. Second, words predicated of God do not mean exactly the same thing in God as when predicated of creatures. Rather, words predicated of God are true of God in ways that transcend the limits of created reality. Take wisdom, for example. When we say, “God is wise,” we are referring to infinite, infallible wisdom. When we say, “The teacher is wise,” we are referring to a finite and fallible wisdom. In any analogy, two things correspond to one another in ways that are similar and dissimilar. In the case of analogical language predicated of God, the two things, words and God, do not bear an exact similitude with no remainder. Rather, the fullness of God’s being transcends the capacity of meaning conveyed by finite words.

The idea that all language about God is analogical stands in stark contrast to two alternative proposals: the theories of univocal and equivocal language. First, if words spoken about God are univocal, then the meaning of the word discloses exactly what is true about God without remainder. The implication of this theory is that God can be comprehended intellectually (i.e., exhaustively understood) by finite creatures. Most theologians in the classical tradition have recognized that this would blur the Creator/creature distinction by reducing the being of God to the level of creatures.

Second, the theory of analogical language stands in contrast to the theory of equivocal language about God. If words spoken about God are equivocal, then the meaning of a word does not disclose anything true about God. To equivocate is to express two altogether different things with the same word. To hold a theory of equivocal language about God would be to embrace a kind of functional deism in which all speech about God is merely a blind guess concerning the reality of one who is utterly unknowable. The analogical theory of theological predication affirms the fittingness of created words spoken about God to reveal truth concerning him (John 17:17) while acknowledging that the LORD’s being is ultimately beyond all comparison (Isa. 46:5, 9) and his ways “inscrutable” on account of his infinite glory (Rom. 11:33).

Proper vs. Figurative Speech about God

Serious Christian thinkers must acknowledge the basic truth of God’s transcendence and creaturely limitations when speaking of God lest they collapse the Creator/creature distinction. A commitment to the analogical theory of language about God has proven to be the most consistent way that classical Christian thinkers have accomplished this. But further distinctions are necessary for a clear understanding of theological language. While all scriptural predications of God are analogical, not all analogical predication in Scripture functions the same way. Some analogical predications are proper, and some are figurative.

As an example of proper predication, consider the divine attribute of power, revealed in such divine names as Creator and El Shaddai (God Almighty). When Scripture speaks of the LORD’s power, it speaks of what is proper to God. Of course, power is predicated of God analogically, not univocally. That is, God’s power is not exactly the same thing as creaturely power. Creatures possess power as an accidental property and in varying degrees. God is power essentially. His power is immutable and without any externally imposed limits. Still, power is attributed to God properly, not figuratively, because creaturely power is a participation in God’s power, not the other way around.

On the other hand, something is predicated of God figuratively if that which is predicated is not proper to God’s being but is proper only to creatures. A reality proper to creatures is used to signify something proper to God by way of the figure of speech. For example, when the prophet Isaiah says, “The LORD’s hand is not short, that it cannot save” (Isa. 59:1), readers should understand that a hand and its relative size are not attributed to God properly. Rather, speaking of the LORD’s hand is a way of signifying his power (which is proper to God) with the imagery of a hand (which is not proper to God). Of course, one knows that a hand is not proper to God because of the clear biblical testimony that God is an infinite, immaterial, invisible Spirit (1 Kgs. 8:27; John 1:18; Rom. 1:19–20; 1 Tim. 1:17, 6:15–16). This is a classic case of an anthropomorphism, a figure of speech in which human body parts are predicated of God. Simple metaphor, simile, anthropomorphism, and anthropopathism (describing God as having human emotions) are among the most common types of figurative theological speech. This form of speech should be carefully distinguished from proper predication. Both kinds of predication are found abundantly in Scripture in reference to God.

The simplest way to describe the difference between proper and figurative predication is to consider which direction the analogy runs between God and creation. The analogical theory of language indicates that there is a comparison between a term predicated of creatures and the same term predicated of God. There is similarity and dissimilarity. The analogical predicate is proper if the notion has its origin in God and its analog in creation. The predicate is figurative if the origin is in creation and the analog is in God.

Thomas Aquinas discusses the distinction between what I am calling proper and figurative predication in his Summa Theologiae. Thomas asks whether names ascribed to God are predicated primarily to creatures. He answers that some things predicated of God are true of God primarily and of creatures secondarily (so the analogy runs from God to creatures), while other things are true of creatures primarily and predicated of God in a secondary sense (the analogy runs from creatures to God). To discuss things true of God primarily, Aquinas appeals to the attributes of goodness and wisdom. Concerning goodness and wisdom, for example, Thomas says, “[T]hese names are applied primarily to God rather than to creatures, because these perfections flow from God to creatures.”[8] Thomas contrasts this mode of predication, which I am calling proper, with another mode of predication in which the names are “applied metaphorically to God,” which is to say, “applied to creatures primarily rather than to God, because when said of God they mean only similitudes to such creatures. . . . Thus it is clear that applied to God the signification of names can be defined only from what is said of creatures.”[9] This is the mode of predication I am calling figurative.

8. Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I. q. 13, a. 6.

9. Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I. q. 13, a. 6.

Reformed thinkers have recognized this distinction as well. Van Mastricht even uses the terms proper and figurative to name these two categories. He says, “Regarding names that are proper . . . theologians observe that in a primary sense they apply to God, and in a secondary sense to creatures.”[10] On the other hand, Van Mastricht states, “[T]he figurative names (as secondary) apply to God either metonymically, when for example he is called our strength, help, light, and salvation (Ps. 18:1; 27:1), or metaphorically, as when he is called a shield or sun (Ps. 84:11; Isa. 10:17), or when these metaphorical names are obtained from man or any other creatures.”[11]

10. Van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Theology, 2:99.

11. Van Mastricht, Theoretical-Practical Theology, 2:99.

Father as Proper Divine Name

Thus far, it has been argued that all scriptural language about God is analogical, but not all analogical language is predicated of God in the same way. Sometimes analogical predicates have their original in God and their analog in creation. This mode of predication is what we are calling proper predication. Other times analogical predicates have their original in creation and their analog in God. This includes many forms of metaphorical speech. This is what we are calling figurative predication. What of the divine name Father? Is father a proper divine name, so that human fatherhood is an analogical participation in what is originally true of God? Or is it a metaphorical name derived from human fatherhood and applied to God as a figure of speech?

The answer to this question is central to evaluating the claims of many that Mother may be used to name God instead of, or alongside of, Father. It is undeniable that motherly figures of speech are used very occasionally to describe divine action in Scripture. Many operate with the uncritical assumption that, in Scripture, motherly imagery and the name Father both occupy the same linguistic and theological space—metaphor. They seem to be unaware of the broader category of analogical language and the important distinction between proper and figurative language under that broader category. Their logic seems to be as follows:

because God is not biologically sexed as male, it follows that the name Father must be a metaphor for God since all created fathers are biologically sexed as male.

However, this line of reasoning assumes that the name Father has creatures as its original designation. That is, it assumes the direction of the analogy runs from creation to God with respect to the name Father. However, if the direction of the analogy runs the other way, i.e., if fatherhood is somehow original to God and is spoken of creatures by way of analogical correspondence, then the name Father is proper to God, not merely a metaphorical figure of speech. Of course, God is not physically sexed as male, but this does not prove that Father is a metaphor. It merely demonstrates that Father is predicated analogically rather than univocally.

In the case of the name Father, Scripture gives a clear-cut statement indicating that it is predicated of God properly. In Ephesians 3:14–15, Paul writes, “For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named.” The word “family” in verse 15 translates the Greek word patria, which means fatherhood. It is true that this word can be a general designation for the family unit as a whole, but this extension of the meaning of the word only makes sense because of the ubiquitous recognition that it is fitting to name the family in terms of its covenantal head.[12] Paul is stating here that fatherhood in creation (“in heaven and earth”) derives its name from God the Father, to whom Paul and all faithful Christians bow the knee. Bavinck captures the sense well:

12. Nearly all the major English translations provide some kind of marginal note pointing out the semantic overlap of the word “father” in v. 14 (pater) and the word translated “family” in v. 15 (patria). The ESV even suggests “fatherhood” as an alternate translation.

This name “Father,” accordingly, is not a metaphor derived from the earth and attributed to God. Exactly the opposite is true: fatherhood on earth is but a distant and vague reflection of the fatherhood of God (Eph. 3:14–15). God is Father in the true and complete sense of the term . . . . He is solely, purely, and totally Father. He is Father alone; he is Father by nature and Father eternally, without beginning or end.[13]

13. Reformed Dogmatics, II:307–8.

Note that Bavinck is recognizing the direction in which the metaphor runs as distinguishing how one should understand the name or attribution. “Father,” he says, is not “derived from the earth and attributed to God.”[14] The opposite is true. The analog runs from God to creation. Centuries before Bavinck, Aquinas cited Ephesians 3:14–15 as a prime example of the distinction between proper and figurative predication as well.[15] Because the name Father has its origin in God and its analog in creation, it is therefore a proper designation for God rather than a metaphorical or figurative one. Once this is understood, all biblically based arguments for referring to God as Mother due to the presence of motherly metaphors in Scripture are exposed as fallacious. Motherly and feminine imagery is used sparingly in Scripture to describe God and his work in the world, but Mother is never properly predicated of God as a name.[16]

14. Reformed Dogmatics, II:307–8.

15. Thomas considers whether all divine names are predicated primarily of creatures and only secondarily of God. In customary fashion, he summarizes three arguments that might suggest all language is figurative. He then answers them thus: “On the contrary, It is written, I bow my knees to the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, of Whom all paternity in heaven and earth is named (Eph. 3:14–15); and the same applies to the other names applied to God and creatures. Therefore these names are applied primarily to God rather than to creatures” (Summa Theologiae I, q. 13, a. 6. Italics in original).

16. In fact, Mother is never predicated directly of God at all, even is a simple metaphor. The motherly imagery for God in Scripture is best described as a kind of simile in which a point of comparison is drawn between motherly action (such as birthing or nursing an infant) and divine action (such as creating or nurturing his covenant people). Far from being an invitation to use the name Mother interchangeably with Father, the Scriptural use of motherly imagery seems to be used more sparingly even than other metaphors in Scripture so that divine revelation is best understood to distance God from the ascription of Mother as a name in any sense.

Essential vs. Personal Divine Names

In addition to the things already observed about divine names, one further distinction needs to be made. Some proper names of God are essential; other names are personal. Essential divine names refer to that by which God is one—the divine essence. Essential names are proper to all three divine persons because all three have the same divine essence. Personal names, on the other hand, name the mode of subsistence of one divine person in relation to another. Personal names are proper to only one divine person because the eternal relation, which is designated by the personal name, is the only feature that distinguishes one person from another in the eternal life of God.

Essential divine names correspond closely to the divine attributes since attributes are predicated of the divine nature and are true of all three persons. As an example of an essential name, consider the sacred name YHWH (often translated LORD), which reveals the aseity and immutability of God (along with the other incommunicable attributes). It is rightly understood to be an essential name. As such, it is true of all three divine persons, a fact Scripture attests by applying the name YHWH to Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.[17]

17. In 1 Corinthians 8:6, the apostle Paul gives a Trinitarian interpretation of the famed Shema in Deuteronomy 6:4, which says, “Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God, the LORD is one.” Paul, contrasting the Christian faith with pagan polytheism, writes, “Yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist.” The one LORD (YHWH) of Deuteronomy 6:4 is understood to be the name of both the Father and the Son in 1 Corinthians 8:6. Paul also identifies the person of the Holy Spirit with the name YHWH when he says, “Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord, there is freedom” (2 Cor. 3:17). Here, Paul uses the Greek word kurios (the “Lord”) to refer to the name YHWH, which follows the standard pattern of his day, as illustrated by the Septuagint. Thus, YHWH, which is predicated of all three persons in Scripture, is an essential name of God, naming that which the persons have in common, the divine essence.

Personal names are fundamentally relational names in that they name the divine persons distinctly by identifying the relations between the persons. The personal name of the first person of the Trinity is Father, and the second person’s personal name is Son. The Father is so named because his mode of subsistence as God is from no one else, but the Son subsists as God from the Father. The names Father and Son do not point out any unique attributes of the respective natures of each person. This would be impossible because they share identically the same nature. Rather, the names Father and Son are distinct only in relation to one another. The meaning of the personal name Father is an empty set except in relation to the Son, who is the eternal “only begotten of the Father” (John 1:14). Concerning the third person, his personal name is Spirit, which translates the Hebrew ruach and Greek pneuma—terms that mean “breath.” As the one “who proceeds from the Father” (John 15:26) and is the “Spirit of his Son” (Gal. 4:6, cf. Rom. 8:9), the Spirit subsists as God breathed out from the Father and the Son. The personal name Spirit does not point out some attribute of the third person’s essence that distinguishes him from the Father and the Son because he shares with them identically the same essence. Rather, the term Spirit is a relational name, which only has distinct meaning when understood in relation to the Father and the Son.

Father as a Personal and Essential Divine Name

The proper divine name Father is both a personal name and an essential name. We have just considered, albeit briefly, the evidence that Father is the personal name of the first person of the Trinity insofar as it names him in relation to the second person of the Trinity, the Son. Considered as a personal name, then, Father is the name of the first person exclusively. However, it is important to recognize that the proper name Father is predicated of God essentially as well. That is, the name Father is a proper name that names God according to his essence, which is common to all three persons of the Godhead. In this essential sense, Father names the triune God in relation to creatures, and the name Father itself reveals the divine attribute of fatherhood.

At least three major considerations need to guide our discussion of Father as an essential divine name. First, Scripture names God as Father in relation to creation generally (see Acts 17:29) and far more frequently in relation to his covenant people specifically. In Deuteronomy 32:6, Moses anticipates a future day of the rebellion of Israel against God. He asks, “Is not he your Father, who created you, who made you and established you?” In Isaiah 64, Isaiah laments the judgment of God on his people and pleads with the Lord to “rend the heavens and come down” (v. 1). In verse eight, he cries out “But now, O LORD, you are our Father; we are the clay, and you are the potter; we are all the work of your hand.” The list of examples could continue, but the point is that the name Father sometimes names the relation of God to creatures. It is in this sense that the name Father is an essential name—true of all members of the trinity. The relation identified is not with one particular divine person as opposed to the others within the eternal life of God. Rather, the relation is between created covenant partners and the one triune God. The triune God is both Creator and covenant Lord of his people.

Secondly, there are even times that Scripture explicitly speaks of the person of the Son as a Father. The most obvious example is the famed messianic prophecy of Isaiah 9:6: “For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (emphasis added). It has been virtually ubiquitous in the Christian tradition to interpret this text as a prophetic foretelling of Jesus. The child born and the Son given is none other than the Lord Jesus, and he is explicitly named “Everlasting Father.” This does not represent a confusion of the persons of the Father and Son because Father, in this context, is not a personal divine name but an essential divine name. The relation named is not the eternal relation between the first and second persons of the Trinity but the relation between the “Everlasting Father” and his people. Thus, it is not a personal divine name. The Son is called Everlasting Father in the same way that he is called Mighty God—essentially.[18]

18. Commenting on the famous Johannine Comma of 1 John 5:7, John Gill says, “The Father is the first Person, so called, not in reference to the creatures, angels, or men, he is the Creator, and so the father of; for this is common to the other two Persons; but in reference to his son Jesus Christ, of whose sonship he bore witness at his baptism and transfiguration on the mount.” John Gill, John Gill’s Commentary of the First Letter of John, ed. Robert A. Edwards (Independently Published, 2023). Special thanks to Daniel Scheiderer for bringing this quote to my attention.

The name Father, as an essential name, reveals the relative attribute of fatherhood. The relation between God and creatures is a relation between the one divine being (who is eternally three persons) and creation. This truth is usually articulated in terms of the classical doctrine of the inseparable operations of the Trinity. Every external work of God is a work of all three persons of the Trinity because the power of the operation is the one power of God.[19] It is not the case that the Father has a distinct work or set of works independent of the Son and Spirit. This would be impossible, because the principle of the external operation is the divine essence common to the three persons. Because creation is a work of God, it is a work of all three persons. Because covenant making is a work of God, it is a work of all three persons. The effect of God’s work—in this case creatures and covenant partners—is in relation to the principle of the work, namely the one God. As such, Father is an essential divine name.

19. For a further description of the doctrine of inseparable operations, see my article, “What God Hath Done Together: Defending the Historic Doctrine of the Inseparable Operations of the Trinity,” JETS 56/4 (2013), 781–800. For a book-length treatment of this classical doctrine, see Adonis Vidu, The Same God Who Works All Things: Inseparable Operations in Trinitarian Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2021).

God as Father and Christian Fatherhood

Thus far, I have argued that Father is a divine name predicated of God properly, not figuratively. Furthermore, I have argued that Father is a divine name in two ways—personal and essential. As a personal name, Father names the first person of the Trinity in relation to the second. As an essential name, Father names the relation between the triune God and creatures and thus is fittingly predicated of all three divine persons. It remains to be considered how human fatherhood corresponds to divine fatherhood considered both personally and essentially.

The eternal relation between God the Father and God the Son is similar to earthly fathers and their children in very limited ways. On this point, the dissimilarities are far more profound. Many of the characteristics of the father-child relationship among humans simply do not pertain to the eternal Father-Son relation in God. Things like authority and submission, provision and need, discipline and sin, and instruction and learning have no place in the eternal Father-Son relation. For this reason, it is really the second way that the name Father is applied to God—essentially—that will be the focus of this section.

Father as an essential name is used most commonly in Scripture to name the relation between God and his covenant people. It is in this sense that we pray to God as “our Father.” If the first person of the Trinity is called Father because he eternally begets the Son, then the triune God is called Father because he adopts his people as sons in covenant relationship with himself. Because of the coming of Jesus Christ into the world to accomplish our salvation and because of the sending of the Holy Spirit into the world to apply redemption to our hearts, Christians are adopted children of God in a permanent way. In Galatians 4:4–6, Paul explains,

When the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God.

Given the covenantal nature of God’s relation to his people as a Father (an essential name), we can begin to discern how human fatherhood analogically corresponds to essential divine fatherhood. Human fathers are created by God to be the heads of their households, governing, providing for, and protecting the inhabitants of their households. Their children share in their estate as heirs. What belongs to the father belongs to the children. The position of covenant head and Lord is one that God has given to human fathers/husbands in a particular way, a way not given to mothers/wives (Eph. 5:22–33).

This brief consideration of the analogical correspondence between Father as a divine name and father as a name given to men is not intended to diminish the tremendous value and dignity of motherhood. Women, like men, are created in the image and after the likeness of God. Mothers, in their mothering, carry out the glorious task of image bearing in ways appropriate to their God-given gender and their God-appointed role in their homes. It is vital for God’s people to remember that there are ways in which it is appropriate and good for mankind to seek to be like God, and ways that are wicked and evil for mankind to seek to be like God (cf. Gen. 1:26–27 and 3:5). When a human person desires to demonstrate the likeness between God and himself through obedience to divine revelation, this is good. When a human person desires to be like God in ways that undermine the authority of divine revelation, this is serpentine. Acknowledging that only human fathers are like God in fatherly ways is a matter of seeking to bear the image obediently and faithfully. Mothers can and should be like God in appropriate ways, but the desire to re-name God as Mother would be to reverse the direction of image-bearing, making God after the image of a creature in the very manner suggested by the ancient serpent.

Conclusion

In an age characterized by the epidemic of fatherlessness coupled with ideological gender insanity, it is not surprising that muddled thinking and misguided teaching abound regarding the fatherhood of God. Much of the confusion can be mitigated if Christians will pay attention to the modes of discourse by which the Bible speaks about God. Such careful attention will lead to the conclusion that Father is a divine name predicated of God properly, not figuratively. As such, it names God in two ways—personally and essentially—both of which find analogical correspondence in human fatherhood.