Not long ago the “New Atheists” were the darlings of new media. Names like Hitchens and Harris, Dawkins and Dennett seemed to be everywhere. One of their principal critiques of Christianity (all religions in fact) was how bad it has been for the world. The subtitle of Christopher Hitchens’s magnum opus was even How Religion Poisons Everything.

1. The Gospels, season 1, episode 10, “Crucifixion and Resurrection,” hosted by Jordan B. Peterson, aired January 26, 2025, on DailyWire+, 1:00:00.

But the nature of media is fickleness. These days it seems Jordan Peterson has singularly replaced the four horsemen and brought a new message: not only is religion good for the world, but specifically “Christianity is necessary, or our culture falls apart.”[2] Such is the driving thesis of the ten-part series on the Daily Wire called The Gospels, where Peterson hosts eight other scholars for a roundtable discussion of the Jesus tradition and its impact on the west. The format is simple: Peterson reads a passage from a Gospel harmony called The Single Gospel: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John Consolidated into a Single Narrative (Neil Averitt; Resource, 2015), and the participants offer observations, reflections, commentary—textual, intertextual, historical, contemporary social, etc.—ask questions, and banter. While the participants vary slightly from episode to episode, most of the lineup is consistent. Robert Barron is a Catholic bishop; Gregg Hurwitz is a novelist and screenwriter; James Orr is a Cambridge professor of philosophy; John Vervaeke is a professor of psychology and colleague of Peterson at the University of Toronto; Dennis Prager is a “religious Jew”; Douglas Hedley teaches philosophy of religion at Cambridge, and particularly interested in Christian Platonism; Stephen Blackwood is the founder of Ralston College; Jonathan Pageau is an Eastern Orthodox iconographer. These make up the panel on the majority of episodes, representing ideas from Judaism to Catholicism, Platonism to Protestantism, Orthodoxy to atheism. Then there is Peterson’s own perspective that is Jungian through and through (more on that below). Yet, even among such diverse perspectives, they all have this same basic concern in common: the western intellectual, aesthetic, and ethical tradition is rapidly eroding, and the secular replacements range from trite to terrifying. Everything comes under the microscope, from pornography and its effects to the horror of the forced labor gulags. The consistent solution around the table—even from the skeptics and atheists—is that everything good, true, and beautiful about western civilization has emerged from the Judeo-Christian tradition. We turn away from that tradition at great peril.

2. The Gospels, season 1, episode 10, “Crucifixion and Resurrection,” hosted by Jordan B. Peterson, aired January 26, 2025, on DailyWire+, 0:57:00.

There is a lot to commend here. It is good to see Christianity—specifically the stories about Jesus—taken so seriously for its intellectual depth and indelible impact it has had on the world. It is also refreshing to observe such an erudite public discourse over the literary-artistic genius of the Gospel narratives. Some of the comments on the texts are very helpful and often quite profound. And I wholeheartedly agree with the understanding that the ideals of democracy, equality, liberty, justice, education, healthcare, humanitarianism, etc. that we so deeply cherish in the west are the collective byproducts of Christianity’s spread throughout the ages.

However, I cannot recommend this series as a helpful guide for understanding the Gospels for three reasons. First, there is so much hermeneutical diversity that it is very hard for viewers to key in on the most helpful ideas. The result is that Peterson’s psychotherapeutic interpretations carry the day because of the amount of airtime he gets. Second, the use of a Gospel harmony—a single basically chronological narrative of Jesus’s life—obscures the particular theological contribution of the four individual Gospels. God’s will for communicating the life of Jesus to the world is through four distinct voices, not through one amalgamation of traditional source material. Much is lost in neglecting this, and this approach actually exacerbates the first problem, creating more space for allegorical interpretations to insert themselves. And third, the series is more a commentary on “the west” and what the participants like about it than it is a reading of the Gospels. But the true telos of New Testament theology, and the ultimate exhibit of its veracity, is not “the west,” but the church and a new creation. I will comment on the problematic nature of each of these in turn.

1. A Sea of Voices

As I mentioned, some of the discussion is quite illuminating, and the recurring emphasis on the Old Testament background is especially helpful. Yet, because there are so many different hermeneutical approaches around the table, and the questions emerge out of such a variety of presuppositional commitments, it is extremely hard to get a handle on what any given passage is really about. Yes, the recurring thesis of the goodness of western society and the requisite Christian foundation is ever present. But therein also lies the problem. It is one thing to say this or that is the result of Christianity; it is another to provide the meaning of Christianity. What are the Gospels actually saying when there are so many takes? When one participant has a legitimate and helpful point to make, it only gets lost in the stew of competing hermeneutical agendas. The average viewer, I believe, gets lost in the sea of erudition—and often esotericism—and comes away still unsure what the passage truly means.

Yet, one voice does rise above the din. Throughout each round of discussion Peterson weighs in with great rhetorical verve. The result is that the viewer mostly hears his take. The viewer is simply confronted with his views far more than the others. It is roughly a 50/50 split between Peterson’s airtime and all the rest combined. That is fine as far as it goes. It is his series; he is the convener; his name is the one that will draw the greatest audience. I have no problem with the proportion of airtime, but with the message that is conveyed when that happens. Peterson clearly reads the Gospels through the lens of Jungian psychology, and also through the idea of archetypal anthropological and sociological forms that he sees channeled through the Gospels and their value for a well-ordered life and society. His Jungian presuppositions are so strong that they dominate the text. He does not listen to the Gospels, but rewrites them in support of his Jungian views.

In so doing, Peterson relativizes the Gospels’ central claims about the exclusivity of Christ and his unique work of redemption. Though I do appreciate Peterson’s emphasis on sacrifice as a grounding narrative, he does not understand Jesus’s sacrifice as either unique or vicarious. Rather the life and ministry of Jesus is an archetypal story full of primordial tropes, and an exemplar of self-discovery and personal improvement—“upward striving” as he calls it.

For example, the ministry of John the Baptist is a demonstration of “conscience preceding the sacred.” It is a neurophysiological and anthropological take on baptism that emphasizes “the transformation of the personality,” the dissolution of the old self and emergence of the new.[3] The annunciation is a philosophical and psychological reflection on motherhood. The beatitudes are about the liberation in letting go of addictions to power, fame, money, and sex. Jesus’s miracles are mythological invitations to “trace how ancient wisdom might illuminate our path from fragmentation to integration.”[4] The resurrection is (perhaps) “the same idea as the impenetrable mystery of the resilience of the human soul . . . Devastated by evil and we can rise up again, the fact that people can pass near death and still live, the fact that we transform and learn continually.”[5] To be sure, much (all?) of the supernatural amounts to “the image of the ideal” that calls us to be something better than what we currently are. The program description to episode nine, called “Betrayal and Trial,” reveals much: “In humanity’s darkest hour, Dr. Peterson’s circle confronts the Passion’s haunting truth: evil triumphs not through villainy, but through good people’s small compromises. Between Gethsemane and Pilate’s seat, they face an eternal question: what price is truth in a world demanding compliance?” Notice that it is not Jesus’s darkest hour, but “humanity’s.” And it is read as a primordial mythos of what happens when people turn from truth through “small compromises” and “compliance.” In the end, the Bible as a whole reveals that “the result of total self-giving is not death but life,” to which Peterson concludes, “That’s like the definition of eternal life.”[6]

3. The Gospels, season 1, episode 1, “Birth – Youth – Baptism,” hosted by Jordan B. Peterson, aired 2024, on DailyWire+, 1:00:00.

4. The Gospels, season 1, episode 3, “Miracles,” hosted by Jordan B. Peterson, aired December 8, 2024, on DailyWire+ (program description).

5. The Gospels, “Crucifixion and Resurrection,” 1:16:00.

6. The Gospels, “Crucifixion and Resurrection,” 1:07:00.

This kind of language is on constant display throughout the series, though much of it is lost on those unfamiliar with Jungian psychotherapy. Yet, there is one back and forth with Dennis Prager where it all becomes a little more explicit. When Peterson is asked about the “road to being good,” he describes it as the “upward aim in [the] grace of God.”[7] Peterson expands, “I came to grips with evil, and I decided I was going to do everything I could to get as far away from that as possible.”[8] He goes on to say that it is something like an encounter with Satan in the desert when he looked at evil so intently. He spent a lot of time studying the Nazi concentration camp of Auschwitz and Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn—not as a detached observer, but as one who wonders what he would have done if he had been there. He concluded that he did not want to be that kind of person, as likely as it is that anyone could become that kind of person. So he committed to head in the other direction. Then, through his reading of Solzhenitsyn and Carl Jung, he learned how to orient himself away from “the lie,” as he calls it, and commit himself to truth-telling.[9] Thus, salvation is from one’s own potential moral decrepitude, and into self-improvement, “upward striving,” “the road to good.” But you have to want it.

7. The Gospels, season 1, episode 8, “Holy Week and The Last Supper,” hosted by Jordan B. Peterson, aired 2025, on DailyWire+, 1:57:00.

8. The Gospels, “Holy Week and The Last Supper,” 1:58:00.

9. The Gospels, “Holy Week and The Last Supper,” 2:00:00.

Within this perspective Jesus ceases to be an historically unique figure, but the “Son of man” and the “logos” are expressions of the essence of humanity, patterns to attain to in our lives. Peterson says, “We call on each other to be a manifestation of the logos.”[10] And “eternal life/the Kingdom of Heaven” is when we attain to this great upward aim in self-sacrifice for each other.

The point is that Peterson’s reading of the Gospels is thoroughly preconditioned by his psychotherapeutic a priori commitments. Then he finds in the Gospels tropes to reinforce that. There is no sense of Jesus as the unique savior who atones for sins in his death or grants eternal life through his resurrection. Rather, Peterson praises Jesus for his constant sacrifice—though it is not a unique or vicarious sacrifice. Instead it is an ideal to which we can all aspire if we too live lives of sacrifice (basically the Peter Abelard reading of the atonement with an existential flare).

10. The Gospels, “Holy Week and The Last Supper,” 1:16:00.

In the sea of voices, this is the one that rises the loudest. It is the lasting impression viewers will have even among many of the other perspectives that to varying degrees align more naturally with the meaning of the Gospels.

Is Christianity true? Well, in Peterson’s final reflection he says it is “the best we have,” and he readily confesses that “it isn’t clear to me how what the Bible portrays is true.”[11] In it all, he reduces the Bible to the same level of many other “mythological texts” (by that I suppose he means the ones he likes) that provide stories for personal and societal “upward striving.”

11. The Gospels, “Crucifixion and Resurrection,” 2:15:00.

To put it simply, Peterson’s interpretation does not square with any Protestant, Catholic, or Orthodox confessional tradition.[12] And it is not a reading of the text, but an imposition of twentieth century psychology onto the text, resulting in twenty hours of Jungian allegory. Jesus is not unique. Jesus is not a savior. The historical nature of the text is not given its weight. The Gospels are not considered on their own terms for their own claims. With such a thick layer of contemporary psychological jargon, the Gospels actually never get a chance to speak.

12. Jonathan Pageau, the Eastern Orthodox, even says at one point that the interpretations provided by Peterson and others on the panel are “weird and different positions” (The Gospels, “Crucifixion and Resurrection,” 2:14:00).

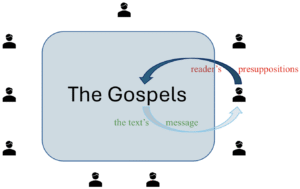

To take a step back, this is an issue of the hermeneutical spiral, and in which direction the interpretive streams of influence are running between reader and text. The series is such that nine men are sitting around a table with the Gospels laid open before them. Each comes with his own presuppositions—ideas about the nature of reality and expectations of what they will find in the text. Then those presuppositions influence what the reader sees. Sometimes, therefore, the text can become a reinforcing mechanism for what the reader already believes. This does not have to be a vicious cycle, however. For the text can change the reader’s mind. But if the presuppositions are too strong, and too controlling, then the opposite occurs. Instead of the text influencing the reader, the reader distorts the text to see what is actually not there. This diagram is meant to illustrate the process. The dark line represents the strength of the presuppositional conviction of the reader, exerting a heavy influence over the reading process. The lighter line represents the influence the text then has back on the reader. It is much softer. The result is that the text is muted, and the reader simply retrieves from the text what he already expected to see.

In such a case the text becomes a mere soundboard for testing, and a prop for supporting, a priori convictions. In short, the text is used, not listened to. Now image nine people doing that at the same time (to varying degrees to be sure) and you get a sense of the hermeneutical chaos on the screen.

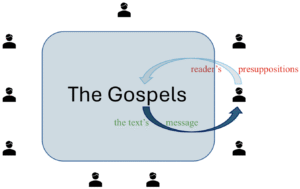

I call this the hermeneutical spiral running in the wrong direction, when readers overlay the text with their philosophical priors, and in turn retrieve from the texts what they already believe. The exact opposite should be happening. If the Bible is the word of God, then we must let it have its way with us. We must listen to it on its own terms and receive from it its own message, not impose our ideas as if it were a plaything in our hands. We must allow it the space to influence us, and change us if necessary. While we cannot jettison our presuppositions altogether, we can hold them loosely and with enough self-awareness that the text can actually influence and mend them. The strength of the lines of influence—what we bring to the text and at what volume the text speaks to us—should run in the obverse direction, as I try to illustrate in this diagram.

This is a hermeneutic of faith, where we let the text’s ideology challenge and change our ideologies, not vice versa. “Follow me” Jesus said, not “take my words and make them fit what you already believe.”[13]

13. Cf. e.g. Matthew 4:18–22; 7:24–27.

As I said, much of the conversation is insightful, with good questions and plenty of food for thought. But Peterson’s comments simply rule the day, and his psychotherapeutic take truly guts the historical and literary search for truth. It all makes it very hard for viewers to discover what the Gospels are really about, even when the other participants often have legitimate interpretations.

2. A Collapsing of Voices

My second criticism is far more basic, but equally important. In fact, it is this shortcoming that opens the door all the wider for the hermeneutical chaos above to ensue. It is this: There are four distinct witnesses to Jesus’s life, not one. To mash them up is to lose the coherent contribution of each in their own right. Several of the participants do comment on this problem, but it is not redressed.

To be sure, there is a long tradition inside the church of creating Gospel harmonies. They can be very helpful for understanding the chronology of Jesus’s life, and comparing the details of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. But there are two problems with relying on harmonies.

For one, they require a reorganization of the original material, creating a new discourse across the whole. Readers are, therefore, already at the interpretive mercy of the compiler/s. Thus, we are back to the first problem above: a set of prior commitments that influence interpretation.

And secondly, such works destroy the structure of each Gospel. Jesus’s biographies are not presented as a list of words and actions in isolated literary units. Rather, each Gospel has an intentional and intricate structure wherein the stories and sayings of Jesus have mutually interpretive power based on the way they are laid next to each other. This is all lost in harmonies, both on the microscale in dealing with each passage, and also on the macroscale in understanding the overall message of each Gospel. The result is that the stories about Jesus are treated in the abstract, not as part of the unified narratives that the original authors intended to present to the world.

Therefore, this series is not a study of the Gospels strictly speaking, for Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are not studied as coherent texts. They are ripped apart and reassembled, then disassembled again in musings over various passages while leaving out much material. It is not a study/discussion of the Gospels specifically, but what we might call “the Gospels tradition.” But then the question re-emerges as above: who puts the tradition together, and on what presuppositional grounds?

This shortcoming actually gives space for the other dynamic to happen at greater scale. By breaking up the structure of each Gospel, dislodging the stories from each other, and vacating the interpretive power the structures have, all the more room is created to insert the determinative presuppositions mentioned above. For the context of each story/saying of Jesus exerts hermeneutical influence, and provides guardrails against misinterpretation. That is all lost when the stories and sayings of Jesus are dealt with in the abstract, detached from their literary settings.

One example will have to suffice that demonstrates both critiques in one place: the withering of the fig tree from Matthew 21:18–22 and Mark 11:12–25. The panel’s interpretations are all over the place. It comes across like grasping, searching their presuppositional pools for whatever will fit from this story. No attention is given to the fact that in both Matthew and Mark the immediate contexts revolve around the temple. Moreover, the cleansing of the temple—right before the cursing of the fig tree in Matthew, and interlaced into the fig tree episode in Mark(!)—cites Jeremiah 7, while Jeremiah 8 uses the image of a barren fig tree to metaphorize the temple leadership. Without going into a lengthy interpretation right here, it suffices simply to note that a contextualized reading of the cursing of the fig tree at least puts the interpreter in a place to discover something of its meaning—in this case vis-à-vis Jesus’s criticism of the temple leadership—rather than scrambling up ideas potentially foreign to both Matthew’s and Mark’s larger theological goals.

We need to remember that the Lord could have given us one super-Gospel, a chronologically straightforward telling of Jesus’s life and ministry. In his providence and wisdom, however, he has given us four distinct witnesses to the life and ministry of the one and only Messiah. We dare not think we are wiser than the Holy Spirit who inspired four Gospels by mashing them all up together, forfeiting the unique structure and voice of each. Jesus prayed for “those who believe in [him] through the [apostles’] word” (John 17:20). Well, that opportunity to believe in Jesus through his hand-picked and authoritative apostles is lost when their diverse voices are crumbled into one reshaped presentation.

3. The Voice of Those Crying in the Wilderness

Finally, we must briefly point out the elephant in the room. Just because the Gospels illuminate what is good, true, and beautiful in western society, that does not mean the Gospels themselves are true. But if the Gospels are true, then we should look to them for what is the telos and goal of their aim. Moreover, if we are talking about letting the Gospels speak to us on their own terms (which is the principal point underwriting my two previous critiques), then we must ask why “western civilization” is used as the yardstick for evaluating the Gospels, or the telos that reveals the genius of the Gospels? The historical horizon beyond themselves to which the Gospel’s look is not “the west,” but the church. The Gospels foresee an international witnessing and worshipping people, who believe in and follow Jesus, from every society across time and space.[14] And their life and love for one another will be the ultimate exhibition of the Gospels’ veracity.[15] The creation of this people, in turn, both inaugurates and foreshadows a new creation.[16] To read the Gospels as a justification and apologetic for “the west” is just another allegory driven by philosophical pre-commitments. The Gospels point us to the church as the place where their teachings are lived out, not “the west.”

14. Cf. e.g. Matthew 28:16–20.

15. Cf. e.g. John 15:12–17.

16. Cf. e.g. John 1:1, 14; 2:11; 17:20; 20:29–31.

Conclusion

The Gospels are perennially susceptible to misuse. But they are also extraordinarily resilient. This is not the first time the Gospels have been put under alien interpretive grids. Surely it will not be the last. Yet, over the ages the voices of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John always seem to come through. Sadly, however, Peterson’s The Gospels is not the place where that happens.

When Peterson comments in this series, he is not commenting on the text of the Gospels, but on his own ideology that he makes the text to fit. Dicing up the Gospels and remaking them into a “single Gospel” makes this all the more possible. The result is missing the point that the church, not “the west,” is the ultimate teleological goal of the Gospels.

Positively I would remind church leaders that in reading the Gospels we must remember our own presuppositions and how they can distort our reading too. We must hold them lightly and let the text of the Gospels speak on their own terms. We must let the Gospels challenge our presuppositions too, and bring every thought captive to the lordship of Christ. We must remember also always to read in context. We must pay attention to passages right before and after our text of study. And we must pay attention to the structure of each Gospel as a whole. In so doing we will see better how the individual stories about Jesus do not float around in the abstract, but come together to develop each Gospel’s unique voice and theology. Finally, we must remember that the world will know that the Father sent the Son through the love his people show for each other. In other words, the evidence of the veracity of the Gospels’ claims is in the church, not in any one philosophical or social tradition, even as that tradition is deeply shaped by the Gospels themselves.